The 1906 Earthquake: "Like a Terrier Shaking a Rat"

Palo Alto was still a young city when it faced its greatest crisis — the earthquake of 1906. While San Francisco and Stanford University suffered more damage, the effect on Palo Alto was severe and extensive. It would prove to be a kind of coming-of-age moment for the new city — the first big test. As it turned out, Palo Altans rallied and immediately vowed to rebuild. Town boosters even saw an opportunity to seize the moment and entice residents fleeing from San Francisco to settle in Palo Alto. While that plan did not succeed, it is clear that the 1906 earthquake did not wreck the city, but rather revitalized it.

At 5:12 on the morning of April 18th, 1906, the earth moved along the San Andreas Fault, and Palo Alto and the Bay Area were rocked by a 47-second, 8.3 magnitude earthquake. Residents awoke in their beds to the terror of trembling floors and falling chimneys. Merchant C.H. Christensen wrote to a cousin in Chicago, “I was lying in bed, half asleep, when I heard a roar in the distance, and before I could get up, the house began to shake with that sinking motion peculiar to earthquakes, and then there came a twisting lurch which did the damage.” Palo Alto resident and Stanford Professor Guido Marx recalled being "rudely awakened by the shaking of the house and the accompanying rumble, roar and crash. ‘What is it?’ said [my wife]. ‘It’s an earthquake and a bad one,’ I replied… I felt nothing could survive such vicious shaking, that this was the end for us. It was like a terrier shaking a rat.” At Stanford, Dr. Olaf P. Jenkins remembered that “Since my bed was walking all over my bedroom and I was sure that the house would land on its side, I just hung on.”

In less than a minute, half the chimneys in Palo Alto had fallen to the ground and nearly every business in town had been damaged. A few buildings completely collapsed, including F.C. Thiele’s new $30,000 store and Fuller’s High Street grocery. The four-year-old Simkins Building lost its first-floor walls, while the two top stories were reported by local papers to be “some three feet out of plumb.” Things weren’t much better at Frazer & Company’s Stanford Building, where the walls fell to the ground leaving early morning sleepers unexpectedly exposed to the elements. Fraternal Hall at 140 University lost its cornice and second story wall, which crashed into Crandall’s Bicycle Shop below. The final bill for Palo Alto’s cleanup eventually totaled more than $165,000 in 1906 dollars.

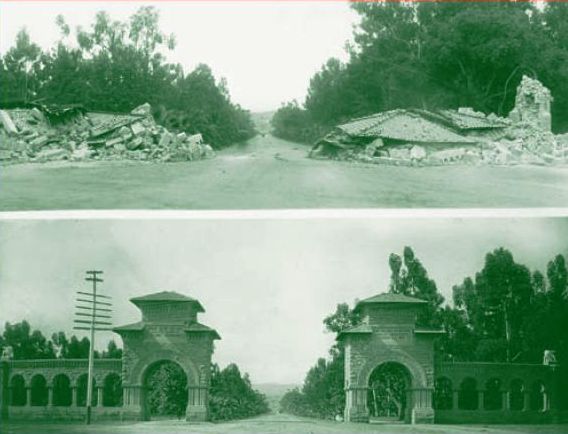

Over at Stanford the damage was even worse. A statue of geologist Louis Agassiz was knocked off its pedestal and crashed headfirst into the pavement below. The façade of the Memorial Church was shattered when its towering spire fell into the nave, the newly completed Stanford Library was utterly devastated, the gymnasium was ruined and the Memorial Arch was cracked and had to be demolished. Reconstruction costs at the university eventually added up to more than $2.8 million.

Two men died in the Stanford wreckage. Sophomore Junius Hannah was hit by a falling chimney at Encina Hall, and a young fireman named Otto Gerdes was struck and killed by the collapse of the 110-foot power house chimney after he raced to the boiler room and heroically shut off campus power.

Palo Alto avoided the catastrophic fires of San Francisco, thanks in part to another brave soul - engineer Robert McGlynn, who was at the Palo Alto power plant when the quake hit. Seeing the sixty foot tower dangerously swaying above him, he had the presence of mind to immediately cut off the town’s power supply, helping assure Palo Alto of water and electricity in the days to come.

But along with such heroics, there was panicky behavior as well. Some Palo Altans raided stores seeking groceries, fearing that they would soon be cut off from San Francisco supplies. Meanwhile at Stanford, an athlete with a loaded pistol reportedly stood on guard protecting female students from “potential rapists,” while armed guards on watch at Palo Alto bridges defended the city from “undesirables and potential burglars.”

As Palo Altans began to right their own lives, their thoughts turned to what was happening to the north. On the evening of the quake, the Palo Alto Times managed — rather determinedly — to get out the paper’s first ever “Extra” by using a hand press and old pied type cases. Its headline spurred action: “San Francisco’s Dead Estimated at 1500; Stricken City in Flames.” The grim portrait soon led to frenzied preparation, as Palo Altans readied themselves for the onslaught of refugees that seemed destined to come their way --- estimates on the day following the quake ran as high as 6,000. This expectation was fueled by the rather remarkable claim that Palo Altans could actually read newspapers from the light of San Francisco fires on the horizon and hear the dynamiting of buildings.

Only about 550 San Franciscans actually took refuge in Palo Alto — but there were enough that the San Jose Mercury and Herald could refer to the city three days after the earthquake as “one grand haven of rest for the sick, homeless and needy earthquake and fire sufferers from San Francisco.” Still, the paper pointed out that “the chief disappointment [Palo Altans] have, seems to be that so few sufferers are coming to [their] doors.”

The evening after the earthquake hit, the Palo Alto and Stanford Relief Committee had been organized at the Circle (near the present day University Avenue underpass). Palo Alto women served 250 to 300 meals each day at the Congregational Church and sewed badly needed baby outfits.

And when it was discovered that damaged rail lines and injuries were preventing many San Franciscans from heading south, volunteers went to the big city, eventually bringing 75,000 loaves of bread, 10,000 gallons of milk and 1,200 sacks of clothing, as well as other badly needed supplies.

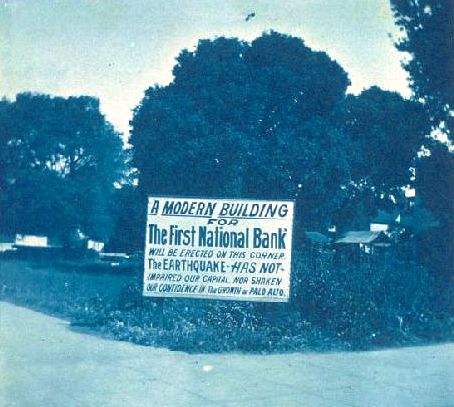

Palo Alto also remained steady in its determination to rebuild following the earthquake. One headline in the Palo Alto Daily Times days after the quake announced “Faith in Palo Alto Unshaken.” The article told of the large sign that had been mounted at the corner of University and Ramona announcing, “A modern building for the First National Bank will be erected on this corner. The earthquake has not impaired our capital or shaken our confidence in the growth of Palo Alto.”

Meanwhile, Board of Trustees President J.F. Parkinson received great cheers from a Relief Committee audience when he told them that, “If I had a dollar tonight, I would invest it in Palo Alto real estate and rest assured that I had acted wisely.” Just two weeks after the earthquake struck, the Palo Alto Tribune told of “work of construction and reconstruction rapidly going forward.” The majority of merchants were back to business as usual within a fortnight.

There were even some town fathers who envisioned the quake as a chance for Palo Alto to achieve some considerable growth. “We will never again get such a chance to boom our town,” Trade Board President Marshall Black declared. Hoping to attract San Francisco residents who might still work in the city but would be looking for homes elsewhere, Palo Alto advertised itself as the perfect commuter suburb. The J.J. Morris Real Estate Company tried to entice potential residents by offering “beautiful cottage homes”at $25 per month and declaring that “This is Palo Alto’s opportunity…The tide of residence travel will turn across the bay and down the Peninsula.”

These efforts were somewhat compromised, however, by a dispute between the city and F.C. Thiele, the owner of a fallen building that stood in ruins just across the tracks from the University Avenue Southern Pacific train station. This disquieting visage led many out-of-town travelers to believe that Palo Alto had fared much worse than it had during the earthquake — a perception problem that eventually prompted city officials to take matters into their own hands. On June 4th, with the building still in shambles, the city ordered workers to clear the debris on the street and throw it back onto the Thiele property at “the owner’s expense.” The Palo Alto Promotion Committee was even planning to erect a large signboard blocking the unsightly building from the view of commuters, when the wreckage was finally cleared up by the owner.

In the end, Palo Alto did not become a booming commuter town following the earthquake, but its real estate market did rebound nicely, business boomed again, and the small town survived that first big test. For sure, the 1906 earthquake had shaken Palo Alto, but it had also stirred resilience and a sense of community pride.

Inside Memorial Church following the earthquake. (PAHA)

The F.C. Thiele Building near the train station was an eyesore and publicity problem for the city of Palo Alto. (PAHA)

A hopeful sign after the earthquake. (PAHA)

The gates at Stanford, after and before (PAHA)

The statue of Louis Agassiz fell head-first to the ground below. (PAHA)

The second floor of the building where Frazer's Dry Goods was located fell to the ground. (PAHA)