The 1967 Recall Election: Palo Alto's Political Rumble

In the late 1960s, America seemed to be coming apart at the seams. A feeling of malcontent and revolt seemed to imbibe the nation as authority was challenged everywhere. In hindsight, the 1960s are often remembered as a time when injustices were overcome, when movements succeeded. And certainly it was. But what is sometimes forgotten was the utter chaos of those times — how in those years it was not always clear if any progress was being made at all. In the moment, it sometimes just seemed that the whole country had decided to pick a fight with itself.

And so it was in Palo Alto. 1967 was the year in which long brewing tensions in local politics finally reached a boiling point. The mood inside the City Council chamber mirrored the times, as new progressives challenged the establishment and chaos reigned supreme.

For years, “representative businessmen” had governed Palo Alto without much opposition. But in the 1950s, Palo Alto grew at a dramatic (some said alarming) rate, doubling in size from a population of 25,475 in 1950 to 52,287 in 1960. Some worried that growth might continue unabated from the foothills to the bay. Ironically, those who first challenged the city’s growth largely came from the newly developed regions outside of downtown. This group, known as the “Residentialists,” favored slower growth and distrusted large commercial and government projects. In 1962, the Residentialists found an issue to rally around — opposition to the highly controversial Oregon Expressway. Although the road was eventually built, Palo Alto’s first anti-establishment political force solidified in the campaign to oppose it.

And soon the Residentialists began to chip away at the Establishment’s power. In 1961, NASA physicist Robert Debs won election as the first Residentialist council member. Two years later he and Enid Pearson led a successful court challenge to the city’s practice of spot zoning and forced the adoption of a Master Plan. Residentialists Kirke Comstock and Phillip Flint were elected to the Council in 1963 and then Pearson, Edward Worthington, and Byron Sher won in 1965. The council was now divided 7-6, with the Establishment holding a narrow one-seat advantage. Tensions were on the rise.

In 1966, gridlock nearly ground the Council to a halt as both sides traded verbal insults and parliamentary procedures. Longtime members Bert Woodward and William Rus regularly referred to the Residentialists as “kooks.” Most important votes split 7-6 and the Council fell more than a month behind its schedule, despite more frequent weekly meetings pushed by Mayor Frances Dias. Walkouts, filibusters, and delaying tactics were common.

In October, things got really out of hand when the majority scheduled a meeting for Halloween night. Protesting that this was an evening that should be devoted to family, the Residentialists boycotted the proceedings. But when Residentialist firebrand Robert Debs showed up to officially lodge his protest, things got ugly. A young reporter at the time, Jay Thorwaldson, described what happened next:

“Debs entered the Council chambers through the side door…He said he wasn't staying, as I recall, but had come to object to a Halloween meeting. Councilman Robert "Bob" Cooley…who was about as feisty as Debs…interrupted.

‘Shove it, Debs!’ he yelled…Debs paused, blinked behind his glasses: ‘What did you say?’

‘I said, 'Shove it!,'’ Cooley repeated slowly.

"Would you like to step outside and say that?’ Debs challenged, flushing. Cooley sprang from his chair, circled behind wide-eyed Council members toward Debs. They started back through the side door, opening a door leading to a rear patio.

But City Manager George Morgan, an ex-Marine, raced to interpose himself between the two. Morgan held them apart as they tried to exit — causing them to bump their shoulders on the door frame. Assistant City Manager Cecil Riley pulled Debs away as Morgan held Cooley, and Debs left, shaking his fist.”

As the tensions rose and the May 1967 election approached, things were looking bleak for the Establishment. Because of a previously mandated council reduction to eleven seats and since more Establishment candidates were up for reelection, the old guard would have to sweep all three seats to hold on to just a one vote advantage. Given the Residentialist momentum in previous elections, this appeared unlikely.

But a bold plan was concocted by Establishment supporter and local attorney William Love. He formed a twelve-member recall committee full of Establishment allies. They would attempt to recall the entire Council — including members of both camps — in hopes of sweeping out most of the Residentialists in one fell swoop.

Pressing the case first articulated in the editorial pages of the Palo Alto Times, Love argued that the Council’s bickering had brought legislating to a standstill. It was time to throw the bums out. By mid-February of 1967, the Recall Committee had managed to collect over 2,000 signatures, enough to put the entire Council up for reelection.

Not all Establishment supporters favored such a strategy. Some Establishment members were outraged at being recalled and three chose not to run again, including Bert Woodward, who said the recall was “a weak and ill-conceived method” of retaliation.

The campaign itself was hectic, as some 21 candidates were running for eleven seats divided into three separate mini-elections: The four-year recall seats, the two-year recall seats, and the seats that would have been up for reelection without the recall. Perhaps exhibiting more seasoned political acumen, the Establishment candidates worked hard to exude a moderate image. Positioning themselves in favor of a “balanced community,” former mayors Frances Dias and Ed Arnold focused their campaign literature on maintaining the “residential character of the city.” They were also able to effectively cast their opponents as rebellious agitators who were responsible for the infighting on the Council. Meanwhile Frances Dias promised to be a “a vote to unify a fragmented city.” While Establishment candidates were certainly richer and slicker, they also benefited from their own political shrewdness.

On the other side, the Residentialist candidates made some political mistakes. Most important were their continued campaign references to the recall issue itself. Although they continually lambasted the opposition for this “Great Recall Robbery,” political observer and future councilman Joe Simitian believes this was unwise. “Since most voters saw it as a fait accompli, the Residentialists reinforced their image of a bickering minority and appeared to be upset only over ‘sour grapes.’” Outraged by their opponents’ political ploy, the Residentialists could never get back on message.

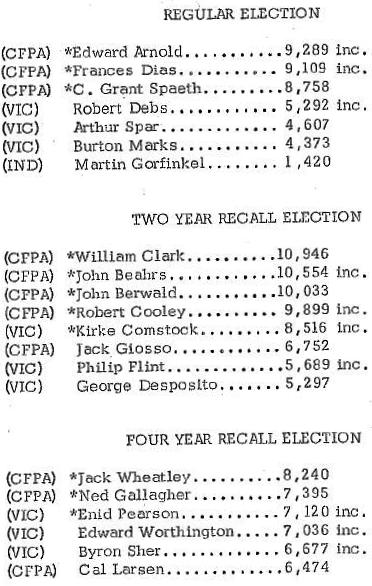

On May 10th, the recall effort proved hugely successful. A record turnout expelled four Residentialist incumbents: Robert Debs, Philip Flint, Byron Sher, and Edward Worthington. Five novice Establishment candidates won council seats: future mayor Jack Wheatley, Grant Spaeth, John Berwald, Ned Gallagher and the election’s top vote-getter: Stanford doctor William Clark. Only the two more conciliatory Residentialists: Kirke Comstock and Enid Pearson were able to hold onto their seats, leaving the Establishment with a 7-2 advantage for the coming session. In the coming decades, the Residentialist movement would take control of city politics for good, winning the battle against entrenched power. But in 1967 — as all hell broke loose in Palo Alto politics — it would be the Establishment that would deliver a knock-out blow.

Our Reader's Memories:

"I got interested in the Council. I was the manager for John Beahres originally. There was a big division and that was a very intresting time. But the two of us almost die when we realized now days that they put a limit of $30,000 on the election. We spent $500 at the most, all we did was make our postcards with his picture on it and send them out and that's all. He just celebrated his 95th birthday. Everybody in Palo Alto was so mad at everybody else. We hated the residentialists and they hated us. My son came up from college to write a paper on it because a recall was so unusual. He got an A on it!"

-Dot

Send Us Your Memories!

The Council Chambers in the old city hall on Newell Road. (PAHA)

Frances Dias in 1969 at a Junior Museum ceremony (PAHA).

The old City Hall which now serves as the city's art center. (PAHA)

Byron Sher in more recent times.

An ad for Frances Dias from the 1967 campaign.

Enid Pearson in 1979. (PAHA)