The Albert Hopkins Beating: The Race Card in Palo Alto

In 2003, the Palo Alto Police Department had its Rodney King moment, as two officers were arrested for beating a black resident on Oxford Avenue. The incident touched off a firestorm of debate over the PAPD’s treatment of African-Americans in Palo Alto.

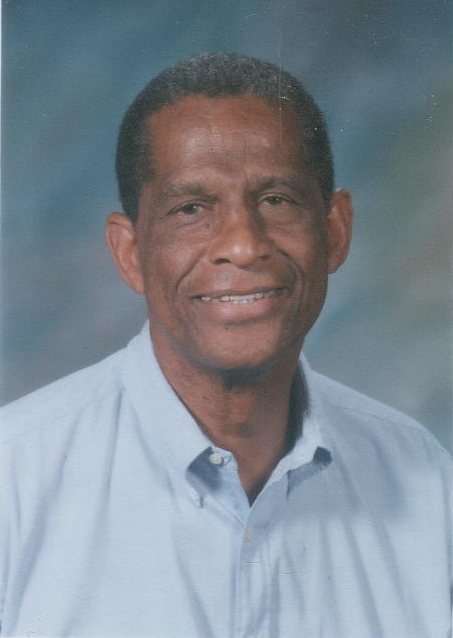

59 year-old Albert Hopkins was a long-time Palo Alto resident. Although he later was a coordinator of the Academic Center at Gunn High School, at the time of the incident he was living in his car, estranged from his wife and working as a desk clerk at the Marriott Hotel. At 10:30 p.m on July 13th, 2003, he was parked at the corner of Oxford Avenue and El Camino Real in Palo Alto, with his foot on the dashboard eating ice cream. 40 year old Palo Alto rookie police officer Craig Lee watched his gray Honda after two residents had called police --- apparently spooked by Hopkins.

After pulling up behind the vehicle, Lee got out to question Hopkins. As Lee approached the Honda, Hopkins jolted his door open, nearly hitting Lee and stood up outside his car. He started yelling at Lee, accused him of racial profiling and demanded that he go away. "A black man can't do nothing in Palo Alto without the police being involved," he said. Lee then ordered Hopkins to get back in his car and close the door. Hopkins got back in, but left the door partially open. Lee then asked for identification, but reached for his gun when Hopkins began to rummage around the clothes-filled car.

Soon fellow officer, 25 year-old Michael Kan arrived and conferred with Lee. They then returned to the car and ordered Hopkins to get out. From this point, accounts differ somewhat. The officers claimed that when Hopkins refused, they pepper-sprayed him in the face and tried to pull him out of the car --- as he tried to pull them in. When they eventually got Hopkins out of the vehicle, the officers said he refused to get down on the ground and that is when they started to use force, beating him with their steel batons and pepper-spraying him again.

Hopkins told the story differently. He said he got out from the car on his own and that when he did, they immediately began beating him "like sharks going after blood in the water.” He was eventually arrested, treated by medics, released and never charged with a crime. Later, Hopkins had surgery for a chipped bone in his knee.

When Hopkins eventually threatened to file charges against the PAPD, The City of Palo Alto agreed to pay Hopkins $250,000 in return for his agreement not to file a civil claim. Still, a criminal trial was yet to come. Kan and Lee were arrested and charged with felony assault and misdemeanor battery.

In the two years between the arrest and the trial, both sides readied their arguments. Lee and Kan claimed they had the right to detain Hopkins because Hopkins was belligerent, did not produce his identification, and acted threateningly. The officers said they acted with discretion, starting with the "lowest level" of force but

eventually resorting to their batons when Hopkins refused to hand over identification or listen to orders. "If Albert Hopkins had obeyed reasonable commands, they wouldn't have used force,'' said Kan’s attorney. Lee’s lawyer added that the allegation of racial discrimination was the "smokiest of smoke screens" and the

"reddest of red herrings."

But many in Palo Alto wondered if Hopkins had been interrogated in the first place due to racial profiling. Since 2000, the PAPD (in an effort to counter the oft-heard claim that they used racial profiling in police stops) had kept track of the race of every person with whom they had come into contact. The results showed that minorities accounted for a disproportionate number of people pulled over by Palo Alto police. Opinions differed greatly over why this was.

And opinions also differed about Palo Alto police behavior, from those who felt the PAPD harassed minorities disproportionately to those who saw them as a heroic thin blue line safeguarding Palo Alto from the criminals of surrounding neighbor cities. The debate overflowed into City Council chambers where many thought the city should do more than just appoint a commission to act as the city’s police review board. The

trial of the officers also created rifts within the PAPD itself. Some officers believed Kan and Lee had reacted appropriately while others were vocal in saying they did not. These were tense days for race-relations in Palo Alto.

As the trial began in 2005, the background of Kan and Hopkins became part of the public record. It came out that Hopkins had been fired from his job as a financial aid officer at De Anza College in 1994 for incidents of sexual misconduct. Lee and Kan’s attorneys also claimed that he had sex with numerous students and was sitting in his car on the night of the incident, “stalking and possibly preying on women.”

It was also revealed that Kan may have been particularly tough on Hopkins in an effort to prove himself to superiors. In May 2003, Kan reportedly watched a fellow officer fight to arrest a suspect, but failed to help. He was ordered to take additional "redman" training -- where he would hold exercises with officers wearing padded red protective suits -- to make him "more aggressive and effective in controlling suspects." When asked how he was doing after beating Hopkins, Kan reportedly told a lieutenant: "I guess I won't need that redman training anymore."

The trial was headline news in Palo Alto and up and down the Peninsula. While cross-examinations were often tense and combative, it was the closing arguments that really stirred the pot. Deputy District Attorney Peter Waite played that ever-present race card, arguing that in some ways the Hopkins beating was worse than Rodney King. While King had committed a crime --- drunk driving --- Hopkins was innocently sitting in his car, Waite argued. Later, he compared Hopkins to Rosa Parks in his refusal to give his identification to officers --- something Waite claimed was not required. “He knew the law better than these bozos,” he told the court. He also weighed in on the debate over Palo Alto’s racial climate. Discussing the two callers who originally called in to police that night, he said, “"Palo Alto, it's the kind of place where citizens --- as is their legal right to do --- call in black people that are walking down the street or sitting in their car.”

The jury deliberated for more than a week before the news was unleashed: The jury was hung. Eight jurors (seven whites and one black) had voted to convict, while four jurors (all Asian) had sided with Han and Lee. Rather than retrying the officers, the two sides eventually came to an agreement. Kan and Lee plead no contest to disturbing the peace and each paid a modest $250 to Hopkins.

But while the case had been settled, the debate over the PAPD had not. Questions about the PAPD’s tactics with people of color still linger and the recent use of controversial tasers have reignited a new debate over Palo Alto's police. []

59 year-old Albert Hopkins was a long-time Palo Alto resident. Although he later was a coordinator of the Academic Center at Gunn High School, at the time of the incident he was living in his car, estranged from his wife and working as a desk clerk at the Marriott Hotel. At 10:30 p.m on July 13th, 2003, he was parked at the corner of Oxford Avenue and El Camino Real in Palo Alto, with his foot on the dashboard eating ice cream. 40 year old Palo Alto rookie police officer Craig Lee watched his gray Honda after two residents had called police --- apparently spooked by Hopkins.

After pulling up behind the vehicle, Lee got out to question Hopkins. As Lee approached the Honda, Hopkins jolted his door open, nearly hitting Lee and stood up outside his car. He started yelling at Lee, accused him of racial profiling and demanded that he go away. "A black man can't do nothing in Palo Alto without the police being involved," he said. Lee then ordered Hopkins to get back in his car and close the door. Hopkins got back in, but left the door partially open. Lee then asked for identification, but reached for his gun when Hopkins began to rummage around the clothes-filled car.

Soon fellow officer, 25 year-old Michael Kan arrived and conferred with Lee. They then returned to the car and ordered Hopkins to get out. From this point, accounts differ somewhat. The officers claimed that when Hopkins refused, they pepper-sprayed him in the face and tried to pull him out of the car --- as he tried to pull them in. When they eventually got Hopkins out of the vehicle, the officers said he refused to get down on the ground and that is when they started to use force, beating him with their steel batons and pepper-spraying him again.

Hopkins told the story differently. He said he got out from the car on his own and that when he did, they immediately began beating him "like sharks going after blood in the water.” He was eventually arrested, treated by medics, released and never charged with a crime. Later, Hopkins had surgery for a chipped bone in his knee.

When Hopkins eventually threatened to file charges against the PAPD, The City of Palo Alto agreed to pay Hopkins $250,000 in return for his agreement not to file a civil claim. Still, a criminal trial was yet to come. Kan and Lee were arrested and charged with felony assault and misdemeanor battery.

In the two years between the arrest and the trial, both sides readied their arguments. Lee and Kan claimed they had the right to detain Hopkins because Hopkins was belligerent, did not produce his identification, and acted threateningly. The officers said they acted with discretion, starting with the "lowest level" of force but

eventually resorting to their batons when Hopkins refused to hand over identification or listen to orders. "If Albert Hopkins had obeyed reasonable commands, they wouldn't have used force,'' said Kan’s attorney. Lee’s lawyer added that the allegation of racial discrimination was the "smokiest of smoke screens" and the

"reddest of red herrings."

But many in Palo Alto wondered if Hopkins had been interrogated in the first place due to racial profiling. Since 2000, the PAPD (in an effort to counter the oft-heard claim that they used racial profiling in police stops) had kept track of the race of every person with whom they had come into contact. The results showed that minorities accounted for a disproportionate number of people pulled over by Palo Alto police. Opinions differed greatly over why this was.

And opinions also differed about Palo Alto police behavior, from those who felt the PAPD harassed minorities disproportionately to those who saw them as a heroic thin blue line safeguarding Palo Alto from the criminals of surrounding neighbor cities. The debate overflowed into City Council chambers where many thought the city should do more than just appoint a commission to act as the city’s police review board. The

trial of the officers also created rifts within the PAPD itself. Some officers believed Kan and Lee had reacted appropriately while others were vocal in saying they did not. These were tense days for race-relations in Palo Alto.

As the trial began in 2005, the background of Kan and Hopkins became part of the public record. It came out that Hopkins had been fired from his job as a financial aid officer at De Anza College in 1994 for incidents of sexual misconduct. Lee and Kan’s attorneys also claimed that he had sex with numerous students and was sitting in his car on the night of the incident, “stalking and possibly preying on women.”

It was also revealed that Kan may have been particularly tough on Hopkins in an effort to prove himself to superiors. In May 2003, Kan reportedly watched a fellow officer fight to arrest a suspect, but failed to help. He was ordered to take additional "redman" training -- where he would hold exercises with officers wearing padded red protective suits -- to make him "more aggressive and effective in controlling suspects." When asked how he was doing after beating Hopkins, Kan reportedly told a lieutenant: "I guess I won't need that redman training anymore."

The trial was headline news in Palo Alto and up and down the Peninsula. While cross-examinations were often tense and combative, it was the closing arguments that really stirred the pot. Deputy District Attorney Peter Waite played that ever-present race card, arguing that in some ways the Hopkins beating was worse than Rodney King. While King had committed a crime --- drunk driving --- Hopkins was innocently sitting in his car, Waite argued. Later, he compared Hopkins to Rosa Parks in his refusal to give his identification to officers --- something Waite claimed was not required. “He knew the law better than these bozos,” he told the court. He also weighed in on the debate over Palo Alto’s racial climate. Discussing the two callers who originally called in to police that night, he said, “"Palo Alto, it's the kind of place where citizens --- as is their legal right to do --- call in black people that are walking down the street or sitting in their car.”

The jury deliberated for more than a week before the news was unleashed: The jury was hung. Eight jurors (seven whites and one black) had voted to convict, while four jurors (all Asian) had sided with Han and Lee. Rather than retrying the officers, the two sides eventually came to an agreement. Kan and Lee plead no contest to disturbing the peace and each paid a modest $250 to Hopkins.

But while the case had been settled, the debate over the PAPD had not. Questions about the PAPD’s tactics with people of color still linger and the recent use of controversial tasers have reignited a new debate over Palo Alto's police. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

Send Us Your Memory!

Albert Hopkins was at the center of the incident at Oxford Avenue.

Oxford Avenue, where the controversial incident took place.

Craig Lee with Michael Kan. (Palo Alto Weekly)

Community members in Palo Alto discussing alledged police brutality. (PA Weekly)