Birge Clark: Palo Alto's In-House Designer

It’s rare these days that a single architect can have that much influence on the look of an entire city. But in days past, before the big architectural firms, sometimes local architects could essentially design their own cities, integrating entire blocks of buildings and giving a city a comprehensive theme. Birge Clark did not lay out Palo Alto in the way that urban grids were surveyed in Washington by Peter Charles L’Enfant or in Philadelphia by Thomas Holme. But he had a major influence over the look of Palo Alto by building many of its most important civic structures and houses --- much as Brasilia’s Oscar Niemeyer or San Diego’s Irving Gill did for larger metropolises. During a career spanning five decades, Clark built 98 Palo Alto houses and nearly 400 buildings in and around town --- including the downtown Post Office, 2 major hotels, the Community Center, police and fire building, Children's Library, the Sea Scout Building and on and on. In many ways what we know as Palo Alto today is a realization of the architectural imagination of Birge Clark.

Birge Clark’s father was an architect, Stanford Professor and mayor of Mayfield. A longtime friend of Herbert Hoover, Arthur Clark constructed the future president’s home in 1919 with assistance from young Birge. After attending Paly High, Stanford and Columbia University, Birge served in World War I, earning the Silver Star for Gallantry after being shot out of an observation balloon by a German pilot and parachuting to safety. Returning home to Palo Alto, he set up shop in 1922, becoming one of just two licensed architects working between San Jose and San Francisco. Like a country doctor, Clark did a little of everything --- houses, schools, public buildings, libraries. And as the city grew in the first half of the 20th Century, Clark was the only architect in town.

He was also immensely talented. In his early days, Clark worked almost exclusively in the fairly short-lived, but locally popular architectural style, variously referred to as Spanish Colonial Revival, California Colonial or the closely-related, Mission Revival. Although there were variations, the style most often consisted of

stucco wall, red clay roof tiles, cast concrete ornaments and wrought iron grilles. Popular between 1915 and 1931, this romantic fashion caught on in many places with a Spanish past --- Florida, Texas and especially California.

In fact, in 1920’s Santa Barbara, the style became so popular that the city government actually legislated all buildings to be constructed in Mission Revival style --- with compulsory specifics written into law. In Palo Alto, the style dominated more naturally, in part because it recalled a Spanish past that were at the roots of El Palo Alto and the city’s founding.

But while Spanish motifs may have been all the rage in 1920s California, things were a little different back East. Presenting his blueprints for Palo Alto’s post office to the nation’s postmaster general in Washington, Clark was ridiculed. As long-time employee and associate Joseph Ehrlich tells the story, “The postmaster

pushed them away and said, ‘Don’t you know what a U.S. post office looks like? We expect a stately building with neo-Romanesque columns showing the power of the federal government. I cannot approve this design.’…Birge responded, ‘Ok, but I don’t think the President and First Lady are going to be pleased with the design change.’” After revealing that the Hoovers had already approved the plans while Clark was breakfasting with his old friends that morning, the postmaster had a sudden change of heart and approved every blueprint in front of him.

During his life, Clark always admitted to being lucky. During the Great Depression when many architects closed up shop, Clark stayed in business in large part doing work for Kaiser Permanente and Palo Alto’s premiere benefactor, Lucie Stern. Thanks to Stern’s generosity, Clark built some of his most memorable structures such as the recently renovated Children's Libary and the Lucie Stern Community Center.

And although Clark became most famous for his Spanish-influenced works like the Roth Building on Homer Street, the Hotel President on University and the Medico-Dental Building on Hamilton, he also ventured into other styles during the later part of his career. His “Streamline Moderne” buildings include the former GM

dealership at 790 High Street and the soon-to-be renovated Sea Scout Building(designed to resemble a ship) out in the Baylands. He also played with the “form equals function” credo of modernism, especially in his work for Hewlett-Packard and Stanford.

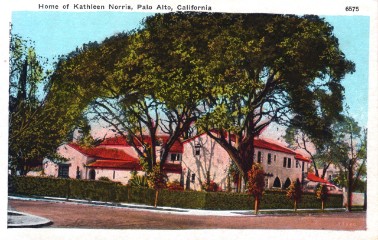

Finally, many of the city’s best known and most prestigious homes were also built by Clark, including the Norris House at 1247 Cowper Street, the Dunker House at 420 Maple Street and Lucie Stern’s own house at 1990 Cowper. And one street still stands as a kind of Birge Clark museum --- he designed every one of

the homes on Coleridge Avenue between Cowper and Webster.

Palo Alto has been called “The City that Birge Built” and the work of his career remains on display all over town. Before his death in 1989, Clark told an interviewer: “You know they say a doctor buries his mistakes, and a lawyer's mistakes go to prison. All an architect has to do to avoid his mistakes is drive

around the block.” Take a drive around Palo Alto’s blocks these days and one thing you won’t find are many Birge Clark mistakes. []

Our Reader's Memories:

"I remember waiting in Grandpa Russ' office after kindergaten (at St Beade's on Sand Hill) while my my mom was busy. It was in the old Spanish style building designed by Birge Clark (Esther's brother). The things I remember most was all the photos on the wall of people he cares about. Also I remember how the receptionist was so gracious a person." -Paul Lee

Send Us Your Memory!

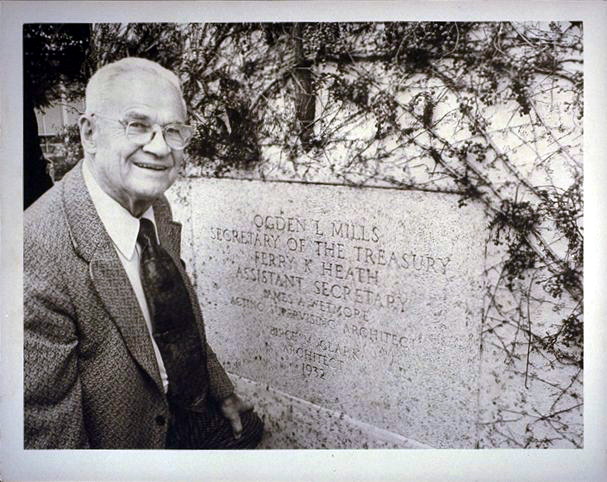

Birge Clark posing outside the engraving at the Palo Alto Post Office. (PAHA)

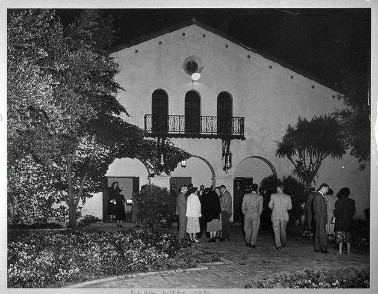

The Palo Alto Community Center in the 1940s.

A postcard of the Norris House on Cowper Street.

Birge posing with wife Estele. (PAHA)

The Hotel President, another Clark design on University Avenue. (PAHA)

The Lucie Stern House as it looks today.