Palo Alto Paternalism: The Hollywood Board

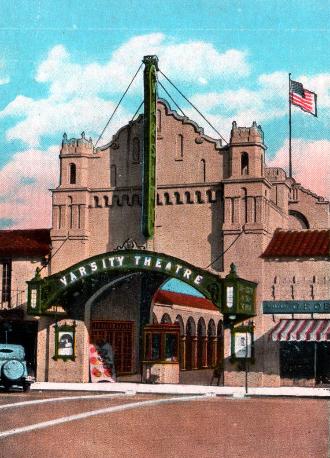

In the early days of cinema, before Hollywood established its own production code to govern violence and sexuality on the screen, the moving picture business was essentially unregulated. Fearing the worst, some localities , including Palo Alto,created their own boards of regulation. Beginning in 1921, the Advisory Board of Commercial Amusements would spend the next three decades holding sway over what Palo Altans could see on the big screen.

Those who remember classic movies as tame soft-focus love serenades may not be aware of Hollywood’s earlier “decade of debauchery.” In the1920s, actresses often appeared on screen in their underwear or even nude, and early talkies used “damn” and “son of a bitch.” On-screen topics included prostitution, homosexuality, illegal drug use and miscegenation. While these no-nos probably wouldn’t make many contemporary moviegoers blush, they were utter blasphemy compared to the conventions of the following era.

A series of scandals inched Hollywood toward the production code. In 1921, Fatty Arbuckle stood trial accused of manslaughter in the death of actress Virginia Rappe at an out-of-control San Francisco party. His acquittal did not erase sensational publicity. The murder next year of director William Desmond Taylor and the revelations about his bisexuality and the drug-related death of actor Wallace Reid in 1923 further demoted Hollywood's reputation around the nation. Throughout the Roaring Twenties, the combination of daring on and off-screen behavior had the public demanding action.

Fearing regulation of the movies from the federal government, Hollywood decided to regulate itself. In 1930, the major studios adopted a Production Code to spell out what was acceptable on the screen. Written by a Jesuit priest (appropriately named Father Daniel A. Lord), Code enforcement began in earnest in July of 1934. It would prove nearly impenetrable for more than 30 years, governing Hollywood films with specific rules banning profanity and nudity as well as edicts prohibiting the portrayal of religious ministers as comic characters or villains. The Code sought to put an end to “morally ambiguous endings” and it was also decreed that the “sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.”

Still, by the time Hollywood got around to censoring itself, cities like Palo Alto already had their own system in place. By its second year, the Advisory Board of Commercial Amusements had already banned all of Fatty Arbuckle’s comedies to date, despite his acquittal. By way of explanation, the Board turned the tradition of “innocent until proven guilty” on its head, maintaining that they would not approve “the showing in Palo Alto of any films featuring any actor or actress who had gained unsavory notoriety by reason of alleged viciousness in private life.”

After the 1920s, the Board put in place a procedure for passing judgment that would last until 1954. On a weekly basis, Board members perused reviews of new films in bulletins such as the confidently-titled, Unbiased Opinions of Current Motion Pictures. If the reviews persuaded three or more members of the seven-member volunteer Board that the film might “tend to corrupt the public morals” then a preview would be ordered --- to be screened at the theatre’s expense, no less. If the Board was restricted a film in Palo Alto, copies of the judgment went straight to the Palo Alto Police. The threat to revoke a theatre’s license for showing the banned movie ensured that in practice theatre owners were always compliant throughout the Board’s 33 year run.

In fairness, the Board was mainly an advisory panel, putting movies into categories such as “family, “young people” or “adults only.” In a number of op-eds and statements over the years, the Board contended that it would not get involved in “Thou Shall Not” censorship, but rather would engage in aiding parents in making informed decisions. Such weekly recommendations were published for many years in the Palo Alto Times and were available at the reference desk at the downtown Carnegie Library.

The Board also kept an eye on horror films. In 1952, the Board asked theatre owners not to double-bill children’s films with adult horror films, as was sometimes the practice on Saturdays. The Board banned outright 38 horror films in Palo Alto between 1943 and 1954. Given that the current rating system of PG-13 and R rated films would not be established for more than fifteen years, it made sense that a civic group would provide this service to Palo Alto parents.

Yet there were many cases where the Board's editing or banning of movies crossed the line into censorship. This was particularly the case in the 1950s. Although by that time Palo Alto was one of just two California cities to have an advisory system in place (the other was in Pasadena), the Board seemed intent on reviewing scenes which challenged the Code.

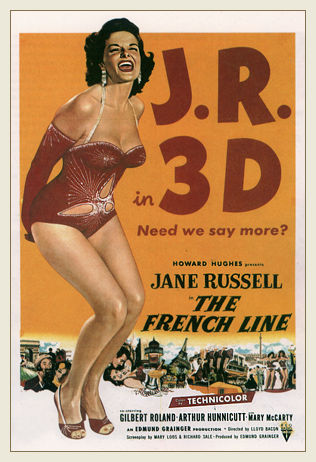

In the late ‘40s, “The Outlaw” and “Duel in the Sun” were banned until certain scenes were snipped. In 1954, “The City Across the River,” “I the Jury,” “Man Crazy,” and “La Ronde” were all banned outright. A film called “Donovan’s Brain” was also censored because of the Board’s questionable critique that “it depicts people as worse than they really are.” The Board also struck down “The French Line,” a Jane Russell film with a plot that seems to have centered a great deal around her cleavage. Sexy vehicles for Rita Hayworth, Jane Russell and Jayne Mansfield had become well known for pushing the boundaries of the Code. Although the Hollywood Production Code did not break until the late 1960s, it began to bend in the 1950s.

Spurred on by a 1952 Supreme Court decision that movies were protected by the First Amendment --- a 1915 decision had found that they were not --- theatres began to challenge the AdvisoryBoard’s authority. On March 4th, 1954, California Avenue's Cardinal Theatre owner Alfred Laurice sued the City in Superior Court, claiming that the Board’s pronouncements violated the Constitution. Among the complaints from Laurice and other theatre owners --- such as George Archibald of the Palo Alto Drive-in Theatre --- was the claim that obligatory previews could cost the theatre owner as much as $50, making it difficult to compete with Menlo Park movie houses that could show the films free of hassle. On March 22nd, City Councilman Lee Rodgers received the backing of the Palo Alto Times editorial page when he offered a motion to abolish the Board entirely.

Indeed, it seemed that the Board’s time had passed. Although it held on for some time in strictly an advisory capacity, the Board eventually stopped meeting altogether. City paternalism, it seemed, had grown out of fashion. Ten years later the Hollywood Production Code would also fall, challenged at first by films from overseas and then by American films made outside the studio system. By the late ‘60s, all bets were off at the movie theatres as a new era of sexual mores was in full bloom. A new era more concerned with personal choice and freedom had begun and anything that smacked of censorship was on its way out. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the first!

Send Us Your Memory!

Jane Russell's The French Line was shown in 3-D in some theatres, but not in Palo Alto.

Comedian Fatty Arbuckle was charged with manslaughter but was later acquitted.

Marlene Deitricht in 1932's Blond Venus.

Barbara Stanwyck in Babyface in which she played a prostitute being pimped by her father.

Mae West made a career of her pre-Code sexuality.