Palo Alto's Civil Defense: Panic After Pearl Harbor

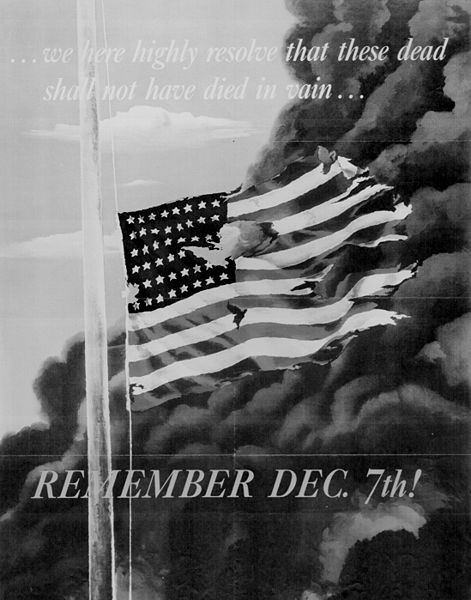

In the confusing days after the December 7th, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, cities all over the Pacific coast were in a state of panic. The destruction of nine warships and 188 aircraft in Hawaii left 2,350 Americans dead and the country greatly unsettled. It was feared that the West Coast stood completely defenseless and terrified civilians braced themselves for the possibility of Japanese troops storming up California beaches. Even when a second wave did not come, Californians continued to maintain vigilant and organized civilian defense throughout the war.

Looked at decades later with a certain amount of victorious historical hindsight, an American continent bordered on both sides by vast oceans seems rather impenetrable. But after the profound shock of Pearl Harbor, the possibility of a Japanese attack on the U.S. mainland seemed all too plausible --- especially in the Bay Area. As rumors were flying everywhere, hours after the initial Japanese strike, a report came into the Army's Western Defense Command that a Japanese fleet was just thirty miles off the San Francisco coast. Sixty Army trucks raced to the water below the Golden Gate Bridge to install antiaircraft guns and by nightfall, every available soldier at the Presidio was digging trenches on the beach.

Meanwhile, on the Bay Bridge, a jittery sentry seriously wounded a female driver who was slow to stop at an improvised checkpoint. Similar episodes played out across the nation. In Los Angeles, antiaircraft battery shot at imaginary planes, injuring dozens of Southlanders as the shells fell upon the city. And as air raid sirens directed citizens on the West Coast to turn out their lights in preparation for a Japanese air attack that never came, a mob of 1,000 angry Seattleites smashed windows and looted stores that remained illuminated. Indeed while Franklin Roosevelt was resolutely declaring December 7th, “a date which will live in infamy,” much of the nation was more than a little frazzled.

Palo Alto also was on edge. In the hours after Pearl Harbor, an antiaircraft battery stood atop a hill near Page Mill Road and what is now Foothill Expressway, searching the skies for enemy attack planes. And like most of the West Coast, Palo Alto stood in darkness that night (and many to follow), as military strategists feared that city lights would provide easy targets for Japanese bombers. Meanwhile, Palo Alto police rushed to secure utilities plants, the water reservoir and the airport, while the City Council met by emergency flashlight. Perhaps some of this local panic was what prompted an editorial in the Palo Alto Times on December 8 headlined, “This is not a time for any form of hysteria; calm and disciplined action is needed now.”

Over the next few days, Mayor Byron Blois set up a committee on disaster preparedness and relief. The committee called for volunteers to serve as emergency police, asking others for voluntary time through a service questionnaire. Meanwhile, Palo Alto Police Chief Howard Zink organized an auxiliary group to support the police, even soliciting donations of “.38 special Smith and Wesson or Colt revolvers…so that men donating their services can be properly equipped.” The Palo Alto Red Cross was also moved to action, asking for the help of “any persons owning station wagons which could be used for emergency ambulances.” Meanwhile a group of 45 “radio hams” organized the Palo Alto Amateur Radio Club to help local relief workers communicate using ultra-high frequency equipment.

Blackouts soon became a regular part of life in Palo Alto. Although University Avenue merchants reported a run on all sorts of blackout materials from dark green window shades to black oilcloth, it took some time for city residents to get accustomed to the practice. “Incomplete cooperation” in three Palo Alto

blackouts on December 9th led City Engineer L. Harold Anderson to write up a list of thirteen rules for air raids to run on the front page of the Palo Alto Times the following day. A few nights later, less than 100% compliance resulted in the plug being pulled on light switches controlling the entire city after just fifteen minutes.

Part of the wayward behavior was probably due to the variation in signals being used in different Bay Area cities. Residents close to the Menlo Park line, for instance, reported a confusing din of various blasts with different meanings on different sides of the border. The City Council had little sympathy, however, imposing a penalty of up to six months in jail and a $500 fine for those who did not comply.

Blackouts eventually became more polished as the Civil Defense Administration in Washington helped unify localities. In Palo Alto, wardens were selected for each block to make sure that all house and car lights in the area were extinguished. The Palo Alto Times of December 30th, 1941 published the official text of “A Handbook for Air Wardens,” which stated their war time mission: “You are the embodiment of all civilian defense…It will be your responsibility to see that everything possible is done to protect and safeguard those homes and citizens from the new hazards created by attack from the air or enemies from within our gates.”

Palo Altans were also trained in what to do if they found themselves in the midst of an attack. On May 11, 1942, for instance, the Palo Alto Times printed a special “Civilian Defense Handbook” edition --- “Study it and keep it near for reference,” a subheadline advised. The special edition was complete with articles from local officials including William Clemo, chief of the Palo Alto Fire Department and Howard Zink, head of the Police Department. One article about poisonous gas cited the expertise of Dr. Charles E. Shepard warning that “it is quite possible that the enemy may use some form of gas to terrorize citizens if

bombing occurs on the West Coast.” The article went on to counsel on coping with mustard gas, describing how to treat oneself with naphtha laundry soap, among other household items.

Another article advised Palo Altans what to do if “a fire bomb pays you a call” and how to set up a “blackout room.” But the paper’s recommendation for how to effectively treat the injured or the ill was perhaps a bit curt --- “Try to take care of the emergency yourself, after all this is war.” And some rather metaphysical guidance appeared on page eight, in which an AP science editor advocated that those on the home front should practice walking blindfolded toward a wall. “You can learn in that way how to sense the wall before bumping against it,” the article reasoned.

As the threat of an actual Japanese attack on American soil began to recede, panic subsided and the nation stirred into action. As the country transformed itself into a wartime economic machine, this industrial juggernaut that FDR called “the arsenal of democracy” would eventually make the difference in providing victory to the Allies.

Still, there is no doubt that in the wake of Pearl Harbor, America reeled in shock as it was drawn out of isolation by a determined foe. Forced to organize itself for war, the nation pulled together and began an epic mobilization and comeback, that transformed the attack on Pearl Harbor from a daringly brilliant military tactic to a decisively dreadful mistake. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

Send Us Your Memory!

Some of Palo Alto's Civil Defense officers. (PAHA)

A photo taken from aboard a Japanese airplane headed toward Pearl Harbor.

A dramatic photo of the exploding USS Shaw.

Americans were asked to "Remember December 7th"

The sinking of the USS California.

Police Chief Howard Zink asked citizens for guns, just in case. (PAHA)