The Embarcadero Underpass: Accident Before Action

Since the days when the automobile first gained widespread popularity, there has been an on-going geographical competition between cars and trains. As roads and highways began to crisscross the land, an emerging web of intersecting pavement met an older web of steel and girders that was the national railroad system. And each time they crossed, there was the potential for disaster, as one form of transportation met another.

Since those early days, eliminating dangerous grade crossings has been on nearly every city and state’s to-do list. Over time, overpasses or underpasses have been built to separate grades at thousands of intersections across the country, but even today, thousands more remain potential danger spots.

Of course, Palo Alto was a train town from the beginning. As the companion settlement to a university founded by a railroad magnate, the city was built around the train depot at the base of University Avenue. Since the onset of the automobile and the construction of its requisite highways and byways, city fathers worried about the intersection of train and car. Originally, these grade crossings consisted primarily of four major intersections --- across Palo Alto Avenue near the Menlo Park border, at busy University Avenue, at California Avenue in the southern end of town and at Embarcadero Road.

It was this last juncture that concerned the most citizens. In 1919, what was then known as Palo Alto Union High School was built at the southeast corner of Embarcadero and El Camino Real just across the train tracks. At the time, this location was a bit out of the way, but it satisfied the political realities of the high school “union” between Palo Alto and Mayfield. Although the two cities would merge entirely in 1925, a central location was of political importance at the time of the school’s founding.

Because more than 250 students reached Palo Alto Union High School by crossing the tracks by either car or foot, the location concerned both parents and school officials. Vague promises were made to build an underpass at Embarcadero Road for cars and pedestrians, but the high school opened in 1919 without one, greatly worrying Principal Walter Nichols.

Before the school even opened, Principal Nichols had embarked upon a determined campaign to try to convince city, state or county officials to build an underpass at the intersection. In a letter to Palo Alto’s Board of Public Safety in July of 1924, Nichols dramatically warned that “It is as certain as the rising sun that a Palo Alto child will be carried home in a hearse from this corner sooner or later.” In his lobbying, Nichols was highly critical of the Southern Pacific Railroad. At one point he incredulously quoted a congratulatory letter he had received from S.P. on the high school’s “efforts to prevent damage to its engines and trains.” He also reported that the railroad had told him that there was no need for an underpass because “thus far there are no fatal accidents that have occurred there.”

At 8:45 a.m. on the morning of October 26th, 1927, seventeen year-olds Mary Collins Harris and Max Springer were on their way to attend the Palo Alto Junior College located on the high school campus. As they reached the rail crossing, flagman Emmet Bennett waved at Springer’s car to stop as the Southern Pacific Shoreline Limited #78 barreled toward the intersection. But for some reason Springer never did stop as his car made the turn toward the high school. As it crossed the tracks, the automobile was struck full-force just behind the rear wheel by the oncoming train, sending the vehicle nearly 50 feet in the air. Both students were thrown out of the car and Mary Harris died instantly. Springer died later at Palo Alto Hospital.

Students at the high school and junior college were devastated. Mary Harris, who friends called “Polly,” was an only child and native of Melbourne, Australia. She had planned to attend Pomona College and was active in the Girl Scouts. Max Springer was the son of prominent Palo Alto Judge John Springer and had been student commissioner of athletics at Palo Alto High School, from which he graduated before continuing on to the Junior College.

On the same day as the horrific crash, bereaved students at the Palo Alto Junior College passed resolutions asking for the immediate construction of an underpass at Embarcadero Road. It read: “Since 1916, the faculty of the high school and the citizens of Palo Alto have consistently urged the construction of a subway. We, being minors, who have no vote, can only protest in this way and petition those whose power is greater than ours to render impossible a repetition of this morning’s tragedy.”

But it would be another nine years before the underpass was built. Not that there wasn’t an effort following the Harris and Springer deaths to remedy the situation. In May of 1929, city voters went to the polls to vote on a $60,000 bond to construct an underpass. Opposing the subway was the Southern Palo Alto Residents Association who believed the project to be “narrow, unsightly and expensive” --- and perhaps a bit too far to the north. On Election Day, despite strong support from the Palo Alto Times and the offer of financial assistance in construction from Southern Pacific, the bond measure fell just a few votes short of the necessary two-thirds majority.

Eventually, it would take the federal government, rather than Palo Alto’s voters to find money for the Embarcadero Road underpass. It would be built as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal effort to lower national unemployment through public works projects. Palo Alto would get a small chunk of the federal government’s $4 million “Grade Separation Program.”

Ten months and $160,000 later, a rather extravagant opening ceremony was held for the unveiling of the underpass. The festivities included a lunch-in at Stanford with appearances by the high school band and local Boy Scout troops. Speeches were given by Harry Hopkins, the chairman of the state highway commission, Palo Alto Mayor Judson and Edward Neron, Deputy Director of Public Works. The Palo Alto Times reported that “the first to traverse the subway were a number of children on bicycles and ‘kiddie cars’ who did not wait for the strains of the anthem to die away to begin the exciting trip.” Addressing the white elephant that hovered over the celebration, Stanford controller Almon Roth assured the crowd that “every family can rest assured that their children will be protected at this crossing.”

Today Caltrain runs on Southern Pacific’s old tracks, Mayfield is but a distant memory to South Palo Altans and the junior college on Paly’s campus is long gone. But the Embarcadero underpass still stands as it has since 1936, an ordinary looking piece of urban infrastructure with a sad story to tell. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

Send Us Your Memory!

The opening ceremony at the underpass. (PAHA)

Under construction.

Palo Alto came out to welcome the much-needed underpass. (PAHA)

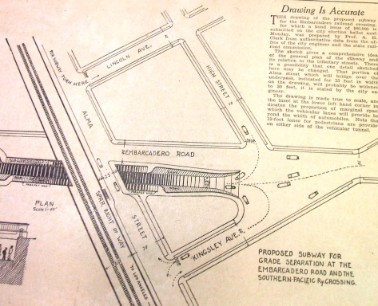

This diagram from the Palo Alto Times shows the layout for the underpass.