The Hotel De Zink: A Friend Indeed

The Great Depression was like nothing America had ever seen. Twenty-five percent unemployment, eleven thousand bank failures, ten years of hard times. Hundreds of thousands of homeless men roamed the countryside, moving from place to place by hitchhiking or hopping trains, begging for food or work in that era before food stamps or unemployment insurance. They were called hoboes, bums, tramps, or stiffs, and by 1931 — as the Depression entered its third dark year — it was becoming clear that hungry men were not going away any time soon. City governments began to contemplate what to do with the jobless men who were wandering into town.

For a time, Palo Alto was one of the most progressive cities in the country in providing a helping hand to men riding the rails. But the institution that led the way in the early 1930’s was not the brainchild of the mayor or anyone else down at City Hall, but rather the inspiration of Mrs. Mable Glover, who first became interested in the plight of the downtrodden while listening to the Amos ‘n’ Andy Show.

Tuning into that famous Depression-era radio serial in 1931, Mrs. Glover heard that many restaurants were throwing away leftover food. After a restless night's sleep, Mrs. Glover went down the next day to ask a number of University Avenue restaurant managers if this was true. When she found out that it was, she and her husband, former sea captain Jesse Glover, petitioned the City Council and Mayor C. H. Christensen for money and space to create a shelter. Its mission would be to “assist worthy men who are in distress…using food which is good and wholesome but unsalable.”

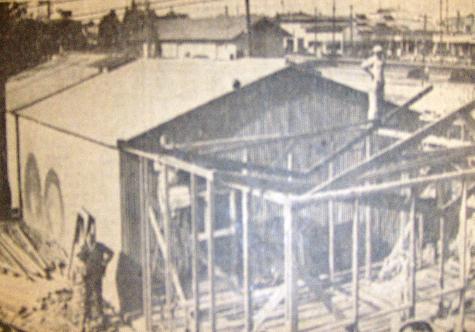

The city pitched in $500, use of a truck and an old warehouse on the Federal Telegraph Company property, where the Sheraton Hotel now stands. Soon private donations came pouring in from benevolent Palo Altans, including famed writer Kathleen Norris. Among the shelter's first donations were a hundred cases of canned goods, a full ton of apples, twenty-five sacks of beets, a live cow and a large bundle of women’s underwear.

On November 9th, 1931, the Palo Alto Shelter welcomed its first “knights of the road,” almost half of whom had served their country in the armed forces. Before long the shelter would become the Hotel de Zink, to honor Police Chief Howard Zink, an enthusiastic supporter of the project and to take notice of the building itself, which was partly constructed of steel galvanized with zinc.

The rules of the shelter were tough but fair. Anyone who stayed at the shelter was required to bathe and delouse but also offered a clean bunk, warm shower, haircut and shave. The hotel’s guests were required to do work around the shelter and help with upkeep. After a three night’s stay, the men were asked to move along. Drunkards were not tolerated and Captain Glover oversaw a tight ship. One itinerant described the scene: “When I entered the shelter last night, the first thing I noticed was the behavior of the guests. Usually the transient is noisy and ill-mannered; here he was quiet and reserved. He talked in a low tone of voice, read the newspaper or played cards. When we lined up for supper there was no crowding or shoving. The food was excellent… After the meal, one of the workers asked that the fellows (and he said, ‘fellows’) pick up the scraps of bread they left at the table. I almost jumped from my seat because he said ‘please.’ After supper, the crew, the guests and Mrs. Glover sat around the fire and listened to music by three artists of the shelter…it seemed as if a shadow lifted from the hearts of those who were there.”

The number of men served by Hotel de Zink was staggering. Records show that in a six-month period from October 1932 to March 1933, the shelter housed some 9, 290 men, served 40,881 meals (plus 8,645 second helpings), repaired 948 pairs of shoes, gave out 1,680 pairs of socks and even provided 111 three-piece suits. The shelter also served the local poor, delivering Christmas baskets, preparing 1,360 lunches for local children and giving out wood and clothes to needy Palo Altans. Shelter services included a small 13-bed hospital overseen by Dr. John Silliman, meals prepared by the former chef of Monterey’s Hotel Del Monte grill (like the Glovers, he took no salary), as well as a shoe repair shop (many men came into the shelter in bare feet), tailor shop, small barber shop, newspaper and dentist.

Sadly, as the Depression wore on, some Palo Altans lost patience with funding the Hotel de Zink. Complaints were heard that the shelter was diverting too much charity to out-of-towners and not enough to locals in need. The shelter was criticized for hiring non-Palo Altans to their staff during a time when jobs were beyond scarce. There were protests demanding that itinerants be sent on to San Francisco or San Jose.

In April of 1934, after two and a half years of serving up and respect to out-of-work men, the shelter was closed down. For another five years, it labored on serving meals in exchange for work. The Glovers continued to give elsewhere to those in need. Mrs. Glover supervised a large San Francisco shelter, while “Cap” Glover helped institute shelters up and down the state.

Today the name Hotel de Zink has been revived by InnVision/Urban Ministry for an emergency shelter that rotates among local churches. Though its scale is nothing like the original, the name is a tribute to Depression visitors and the Palo Altans who met each other at the old shelter. For some of the 50,000 weary men it served, the first Hotel de Zink was remembered as a comfort to them in their hardest days. One man later wrote to Captain and Mrs. Glover: “To the best friends I have. May your years be long and happy and you enjoy life and may God bless you. As a friend in need, you were a friend indeed.”

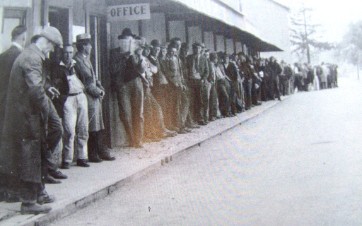

A line of men waiting outside the Hotel De Zink. (Courtesy Palo Alto Historical Association)

A barber gives a guest a haircut. (Courtesy Palo Alto Historical Association)

The original construction of the shelter in 1931.

Cap and Mable Glover.

Chief Zink, the shelter's namesake. (Courtesy Palo Alto Historical Association)

An editorial cartoon from the Palo Alto Times commenting on the shelter.