Japanese-American Internment: Palo Alto's Deported Patriots

Civil liberties often suffer duringwartime, a fact that maycontradict the ideological and moral justifications for the wars being conducted. Early patriots passed the highly repressive Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798 to protect against “alien citizens of enemy powers.” Abraham Lincoln, in the midst of saving the Union and ending slavery during the Civil War, suspended the right of habeas corpus. At the beginning of the Cold War, as America began a half-century of struggle to bring down the iron curtain of Stalinist communism, a red scare at home led to McCarthyism, blacklists and the kind of government authoritarianism that reminded many of the Soviet system itself. And in 2001, the U.S. responded to 9/11 with a war on terror to defend America’s “way of life,” certain freedoms that defined that way of life were being curtailed by the Patriot Act.

Of course, there is a natural tendency for governments to scale back civil liberties during the tension and hysteria that accompanies war. It was in such an atmosphere following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 that the American government committed its most shameful act of wartime repression --- the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans. Indeed, while “the Greatest Generation” made our nation proud fighting in the Pacific and on the beaches of France to liberate Europe from one of Earth’s all-time dictators, the country’s moral righteousness was tainted by its actions at home.

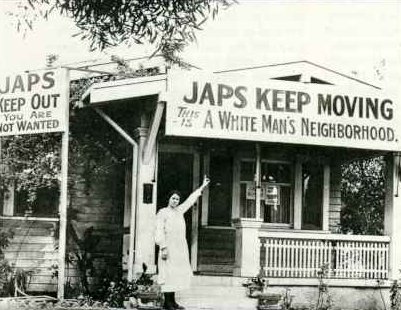

In the months that followed the surprise Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, America braced itself for a potential follow-up attack on its own shores. It was in this environment that a range of hostile reactions from suspicion to outright racism were directed towards the Japanese-American community. Some West Coast leaders and media organizations questioned the loyalty of Japanese Americans, and these flames were fanned by groups of California farmers who cynically saw a chance to obtain profitable Japanese-American farmland. Under pressure, the government slowly began to move toward a policy of outright internment based on ancestry.

In Palo Alto, the small Japanese-American community of about 200 began to worry about their future. In March of 1942, all local Japanese Americans were ordered to register their property at Police headquarters on Bryant Street. In April, an 8 p.m. curfew was imposed exclusively on Japanese Americans, and by the middle of June there was not a single Japanese American left in Palo Alto.

Immediately following Pearl Harbor, many of Palo Alto Japanese Americans feared the worst and some even pleaded their patriotism. Arthur Okado’s family had been in America since 1909. But two days after Pearl Harbor, the President of the Palo Alto Japanese-American Association released a statement printed in thePalo Alto Times, saying “We the members of the Japanese-American community having lived in Palo Alto and Menlo Park throughout 40 years…wish to make our stand clear. Without reservation, we are loyal to this, our country, the United States of America.”

The article went on to say that the members of the association had purchased some $2,700 in defense bonds and that seven of their men were serving in the Army --- including Paly graduate Fred Yamamoto, who would posthumously win the Silver Star after dying in France. Still, 10 weeks later, Mr. Okado was arrested by FBI agents, along with three other Palo Altans on suspicion of belonging to an “alien Japanese organization.” It wasn’t until February 1945 that he would return home to Palo Alto cleared of all suspected wrongdoing.

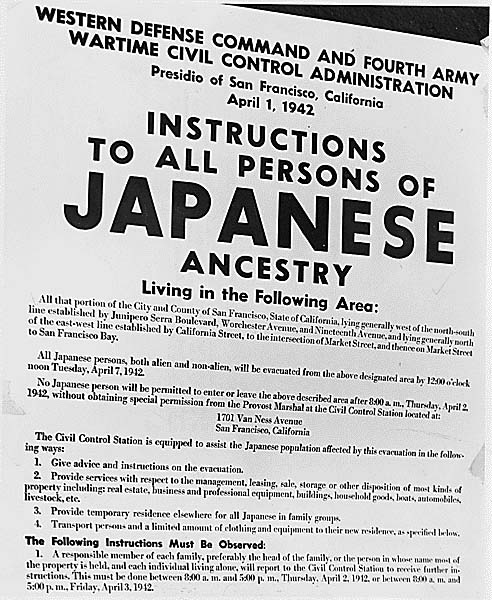

On May 19th, 1942, all Japanese Americans were ordered to leave Palo Alto and the West Coast by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt upon the authority of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Later, Dewitt defended his decision saying, “A Jap’s a Jap. We must worry about the Japanese all the time, until he is wiped off the map.”

Palo Alto Japanese Americans had less than a week to sell their homes, farms and businesses --- just a small portion of the $400 million nationwide (in 1942 dollars) that Japanese Americans would lose because of the internment. On May 26, 144 local Japanese Americans boarded buses leaving for the former racetrack that had been euphemistically renamed the Santa Anita Reception Center. Each person was only allowed to take as much as they could carry. An animal ban meant that most family pets had to be destroyed. Japanese Americans and their Caucasian friends exchanged candy, oranges and other small mementos, while the Palo Alto Society of Friends and the Gray Ladies of the Red Cross brought refreshments, lunch and milk. Then the buses pulled away and they were all gone.

The Palo Altans spent the next few months at Santa Anita before most were moved on to Heart Mountain Relocation Center near Cody, Wyoming. John Kitasako described the scene as they left for Wyoming: “The farewells at the trains are pathetic. Separated friends and even families will not see each other again for the duration [of the war].”

The internment train rides were often horrific. Palo Altan Cherry Ishimatsu would later describe her ride to an Arkansas internment camp: “It was very frustrating, very difficult and a very traumatic experience. It must have taken nine days. The sanitation of the train that you cannot get off of for nine days is horrendous. It was a nightmare.” She added that it was extremely hot, the windows were shut for the entire ride and hardly any light reached the inside of the train.

Spirits improved little when most of the Palo Altans reached their final destination and joined 10,000 other Heart Mountain internees. Kitasako reported back to Palo Alto that “our first impression of this center was disillusioning…We could not help but feel we were cut off from the rest of the world.” The grim barracks behind barbed wire were primitive at best. The toilets were not partitioned, the beds were simple cots, and the daily budget for food rations was 45 cents per capita. Even Kitasako, an eternal optimist, lamented that “The psychological effects of our confinement have complicated our mental and spiritual structures. We must bolster our morale, we must shake off the outgrowths of penal complexes.” More than any hard times or economic loss, most internees remember that the worst part of their experience was the indignity of being treated as a criminal in their own country.

Despite the shame that the nation must bear for the entire internment episode, there is evidence that Palo Alto’s record of tolerance in those years was commendable --- at least by the standards of 1942. There are few recorded instances of prejudice from locals, and many Caucasians were later honored by Palo Alto Japanese Americans for their help --- visiting and volunteering to teach in the internment camps, sending books, toys, clothing and later providing legal help.

The press of the day also demonstrated sympathy for Palo Alto’s friends and neighbors of Japanese ancestry. Paly’s newspaper “The Campanile,” reminded readers in 1942 that “They are Americans too…Give them a farewell that will make them want to stay Americans!” And the Palo Alto Times opined in May that, “When Japanese and Japanese-Americans leave Palo Alto this week, the loss will be ours as well as theirs…Our hearts go out to them in the sorrow and hardshipof the uprooting.”

Additionally, in the year following the war, James E. Edmiston of the War Relocation Association stated that “no city has done a more complete job than Palo Alto…in helping Japanese and Japanese-Americans reinstate themselves in the community.”

Still, few Palo Altans protested or seriously questioned the orders of their government. The Times called the policy the “lesser of two evils,” believing that it was “necessary for the safety of us all.” It was until 1988 that Japanese Americans nationwide would receive an official apology from their government. The Civil Liberties Actof 1988 acknowledged “the fundamental injustice of the evacuation, relocation, and internment of United States citizens and permanent resident aliens of Japanese ancestry”and provided redress of $20,000 for each surviving detainee.

For many, the legacy of the internment tragedy is the unwavering humanity of the Japanese-American people, as much as the inhumanity of the government that incarcerated them. A few days before the Palo Alto Japanese Americans were to be forcibly removed from their home --- on a day when anger and hurt must have been raging inside each of them --- they sent this letter to the Palo Alto Times:

“To the Palo Alto Community:As we leave we would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the many American friends of this community for their kindness, understanding and fair-mindedness…Needless to say, we are sorry to leave Palo Alto...Many of us have been born here, most of us have gone through all the schools here and some have gone through the university. However, the sorrow that we feel is alleviated in the knowledge that by evacuating, we are cooperating and aiding in the United States’ war effort…As we close, we wish to express the hope that we may soon renew our friendship and become part of this community which we regard as our home. We hope that we have been able to express our gratitude for the friendship given to us by the people of this community.”

It seems unlikely that any American could love their country more than this. []

Our Reader's Memories:

"I just wanted you to know that, as usual, you have brought attention to another sad and sorry episode in our country's history. We have Japanese friends and I always felt so somehow responsible about that episode - partly because we didn't do anything about it, though I think it wasn't really possible to do anything, except to listen. And now I'm afraid the same prejudice may be used against any Arabs who have settled in the U.S., though they probably would not have anything to do with the violent, fanatical Muslims. But thanks again, for your interesting stories."

-T

"I was 6 years old when my parents, 2 brothers and sister where sent to Manzanar. From there we were transferred to Tulelake. My father was sent to Santa Fe and my mother was left with us and 2 babies which made 6 young children alone with her. We were united aboard the MATS ship General Gorden in Dec. 1946 where my parents went to Japan. That same year January they lost my brother, 2, and sister, 12 months old. My mother passed away Sept. 11, 2007. My father worked as a translator for the Sugamo prison for the Japanese POW. His name was Kanjiro Haimoto. He passed away at the age of 48 in Dec. 1954."

-Jeanette

"Wow, we are trying to find the two wonderful Japanese ladies, who were quite young then and who worked for my grandmother who was well known in California circles. My grandmother's name was Laura O'Hanlon/Hanlon Meek, Bert B. Meek's widow, assemblyman, and CA Director of Public Works, VP of WR Hearst, etc. Later my grandmother became Laura Hanlon Edwards when she married Emmett Edwards of the Alisal Ranch. My grandmother and mother and their family lived at the Janin place, which they bought and was in this area. Mom, Loree (Laura Marie) Meek I think went to Palo Alto High and then on to Stanford in 1939-1940, where she graduated during WWII. The two Japanese ladies were adored by mom's family and the children esp. were deeply saddened by their departure. My mother mentioned finding them to the end of her life. I have nothing to go on but some dates and places. Does a list exist anywhere for the families that went into these camps from Palo Alto? I would be so appreciative if anyone knew where to start. Thank you! "

- Virginia

Send Us Your Memory!

The Japanese Association of Palo Alto marches in Dedication Day Parade just months before being deported. (PAHA)

Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming.

Marching on Dedication Day in 1941. (PAHA)

Signs like this were not uncommon in the United States in the days following Pearl Harbor.

A notice following Executive Order 9066.