The Lytton Plaza Protests: Rebels Without a Cause

The 1960s and early ‘70s were a time

when many Americans took to the streets to protest the injustices they saw in the society around them. Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks and

black bus riders in Montgomery, Alabama famously ushered in an era

of protest in a year-long bus boycott beginning in December of 1955. More formalized marches, sit-ins, be-ins and other acts of civil

disobedience led the fight for black and

women’s civil rights and the fight against the war in Vietnam. Protesting in America in those years was often a sign of the aware and educated citizen who wanted to change society for the better.

But not all young people took to the streets in those years for worthy causes --- and once they were in the streets, not everyone behaved themselves. Some protesters had little political awareness or sense of civic duty, simply using the chaos of the demonstrations to vent anger, cause trouble and antagonize police.

Unfortunately, the legacy of Downtown Palo Alto’s Lytton Plaza is more of the rowdy troublemaker than the educated dissenter. Not to say that Palo Alto has not had its share of both peaceful and enlightened protests. But especially between 1968 and 1972, Lytton Plaza became famous for a series of chaotic riots that symbolized the worst of the youth movement, not the best.

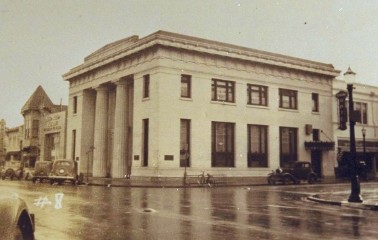

The former location of the monumental American Trust Building, the 8,500 square foot plaza was constructed in 1964 by Bart Lytton across the street from his Lytton Savings Bank at Emerson and University. With its brick and cement foundation and modernist rounded concrete bench/plant holders, the plaza always had a somewhat severe appearance. Still, at its inception in 1964, it was clean, well-groomed and a needed pedestrian oasis in an increasingly automobile-centered downtown.

But while Lytton intended the plaza for the “use and enjoyment of the people of Palo Alto,” some people’s idea of “enjoyment” was not exactly what Lytton had in mind. Within five years, the plaza had become the favored spot in Palo Alto for both protest and late-night rock concerts. Because it was privately owned, it was not subject to city park regulations, and because it was not fenced, anti-trespass laws did not apply. As a sort of legal “no man’s land,” Lytton Plaza soon became the place to challenge the system in Palo Alto.

The leftist Midpeninsula Free University (MFU) first took advantage of Lytton Plaza’s in-between status during the summer of 1968. After staging a series of rallies and music concerts there --- some of which had resulted in police intervention --- downtown business had grown weary of the new MFU scene at the plaza. The Palo Alto Times reported that summer that 63% of downtown merchants wanted the plaza closed and 86% favored the police stopping the demonstrations.

Lytton and his bank responded to business concerns by posting a list of rules at the plaza. Reiterating that the land was owned by Lytton Savings, the poster stated that music and crowds over 25 people were prohibited except through the permission of the bank. The poster was soon graced with an expletive-laced response.

By 1969, Saturday night rock concerts with live bands were commonplace at the plaza, many sponsored by the “Free People’s Free Music Company” run by Paly teenagers. One summer concert devolved into mayhem when a motorcycle gang began numerous fist fights and scuffles with the largely hippie high school crowd.

Later that summer, 4 people were arrested on drug possession charges after a fight ensued and 17 arrests were made on liquoring and loitering charges. Arrests, drug use, fistfights and loud music became commonplace at Lytton Plaza, drawing further ire from local merchants. Peninsula Creamery owner Doris Christensen told the Times that summer that “The elderly are afraid to walk downtown for fear they’ll be manhandled. It’s a disgrace for anyone to call policeman ‘pigs.’ Let’s say no more be-ins. We merchants have our rights too.” The cultural divide was alive and well in Palo Alto.

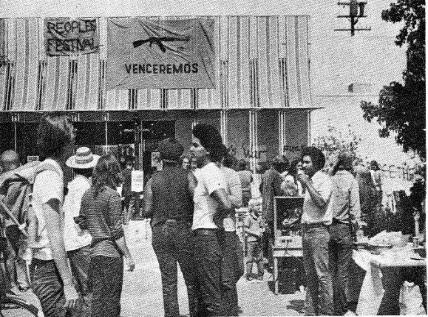

By the summer of 1970, the radical Marxist group Venceremos, the White Panthers and the Bay Area Revolutionary Union had all gotten involved. In fact, by this third summer of tension, Lytton Plaza was drawing local high school teens, radical leftists, college protesters, hippie drop-outs and rowdy drug-pushers to what was becoming a kind of beacon for Bay Area counterculture activity.

At first the city tried to get tough. When the City Council passed an ordinance restricting amplified music after 11pm, the police intended to uphold the letter of the law. And uphold it, they did. On July 11th, 1970, 263 people were arrested, including members of the band, when the music went on past the forbidden hour. A full scale riot was only prevented by a pepper gas machine that left a foot-and-a-half high fog that emptied Lytton Plaza.

The following week after 300 people showed up at Palo Alto City Hall to condemn the mass arrests, leftist groups vowed to liberate the plaza. MFU leader John Dolly told the press that “In response to the astounding increase in fascist police tactics being used in Palo Alto, we are calling for all concerned brothers and sisters from San Jose to Berkeley to help us claim downtown Lytton plaza.” Meanwhile Vencremos began calling it the “People’s Plaza,” and encouraging their membership to bring weapons to “fight the pigs.” Soon many demonstrators were carrying mace, baseball bats and other increasingly hostile weapons --- not a good sign given that a rifle was the official Venceremos logo.

Two Saturdays later, under guidance from Mayor Jack Wheatley and City Manager George Morgan, police tried backing off. More than 200 officers watched from a distance as a rock band played on until 1 in the morning.

But many radicals wanted to draw police into a confrontation. In August 1971, students at the Plaza goaded police in a series of escalating steps. As then reporter Jay Thorwaldson described, “between each step, there was a few minutes wait, either to build up nerve for the next step, or more likely, to see if there would be a police response.” After starting several trash fires and pulling a number of false box alarms, demonstrators blocked Emerson Street with a bicycle rack, dumped over a trash bin, severely damaged and set a newspaper rack ablaze. They then set out to break more than $24,000 worth of windows along University Avenue. Weeks later more than 20 trash containers were set on fire and rioting concert-goers broke light fixtures and defaced property with slogans like “Kill the pigs.”

While things finally began to calm down over the next summer, the legacy left at Lytton Plaza was not exactly the soulful refrain of “We Shall Overcome.”

Eventually, Lytton Savings Bank was bought out and the city purchased the space from its new owner. Since those days, Lytton Plaza has continued to be Palo Alto’s traditional place of protest, although it’s been some time since the teargas machines have been needed.

Recently, there have been plans bouncing around City Hall to tear up Lytton Plaza and replace it with a new park full of leafy trees, pretty hedges and a waterfall. Gone will be the cement benches and concrete austerity. Perhaps it will be a new start for the aging plaza with so many memories that no one particularly wants to remember. []

women’s civil rights and the fight against the war in Vietnam. Protesting in America in those years was often a sign of the aware and educated citizen who wanted to change society for the better.

But not all young people took to the streets in those years for worthy causes --- and once they were in the streets, not everyone behaved themselves. Some protesters had little political awareness or sense of civic duty, simply using the chaos of the demonstrations to vent anger, cause trouble and antagonize police.

Unfortunately, the legacy of Downtown Palo Alto’s Lytton Plaza is more of the rowdy troublemaker than the educated dissenter. Not to say that Palo Alto has not had its share of both peaceful and enlightened protests. But especially between 1968 and 1972, Lytton Plaza became famous for a series of chaotic riots that symbolized the worst of the youth movement, not the best.

The former location of the monumental American Trust Building, the 8,500 square foot plaza was constructed in 1964 by Bart Lytton across the street from his Lytton Savings Bank at Emerson and University. With its brick and cement foundation and modernist rounded concrete bench/plant holders, the plaza always had a somewhat severe appearance. Still, at its inception in 1964, it was clean, well-groomed and a needed pedestrian oasis in an increasingly automobile-centered downtown.

But while Lytton intended the plaza for the “use and enjoyment of the people of Palo Alto,” some people’s idea of “enjoyment” was not exactly what Lytton had in mind. Within five years, the plaza had become the favored spot in Palo Alto for both protest and late-night rock concerts. Because it was privately owned, it was not subject to city park regulations, and because it was not fenced, anti-trespass laws did not apply. As a sort of legal “no man’s land,” Lytton Plaza soon became the place to challenge the system in Palo Alto.

The leftist Midpeninsula Free University (MFU) first took advantage of Lytton Plaza’s in-between status during the summer of 1968. After staging a series of rallies and music concerts there --- some of which had resulted in police intervention --- downtown business had grown weary of the new MFU scene at the plaza. The Palo Alto Times reported that summer that 63% of downtown merchants wanted the plaza closed and 86% favored the police stopping the demonstrations.

Lytton and his bank responded to business concerns by posting a list of rules at the plaza. Reiterating that the land was owned by Lytton Savings, the poster stated that music and crowds over 25 people were prohibited except through the permission of the bank. The poster was soon graced with an expletive-laced response.

By 1969, Saturday night rock concerts with live bands were commonplace at the plaza, many sponsored by the “Free People’s Free Music Company” run by Paly teenagers. One summer concert devolved into mayhem when a motorcycle gang began numerous fist fights and scuffles with the largely hippie high school crowd.

Later that summer, 4 people were arrested on drug possession charges after a fight ensued and 17 arrests were made on liquoring and loitering charges. Arrests, drug use, fistfights and loud music became commonplace at Lytton Plaza, drawing further ire from local merchants. Peninsula Creamery owner Doris Christensen told the Times that summer that “The elderly are afraid to walk downtown for fear they’ll be manhandled. It’s a disgrace for anyone to call policeman ‘pigs.’ Let’s say no more be-ins. We merchants have our rights too.” The cultural divide was alive and well in Palo Alto.

By the summer of 1970, the radical Marxist group Venceremos, the White Panthers and the Bay Area Revolutionary Union had all gotten involved. In fact, by this third summer of tension, Lytton Plaza was drawing local high school teens, radical leftists, college protesters, hippie drop-outs and rowdy drug-pushers to what was becoming a kind of beacon for Bay Area counterculture activity.

At first the city tried to get tough. When the City Council passed an ordinance restricting amplified music after 11pm, the police intended to uphold the letter of the law. And uphold it, they did. On July 11th, 1970, 263 people were arrested, including members of the band, when the music went on past the forbidden hour. A full scale riot was only prevented by a pepper gas machine that left a foot-and-a-half high fog that emptied Lytton Plaza.

The following week after 300 people showed up at Palo Alto City Hall to condemn the mass arrests, leftist groups vowed to liberate the plaza. MFU leader John Dolly told the press that “In response to the astounding increase in fascist police tactics being used in Palo Alto, we are calling for all concerned brothers and sisters from San Jose to Berkeley to help us claim downtown Lytton plaza.” Meanwhile Vencremos began calling it the “People’s Plaza,” and encouraging their membership to bring weapons to “fight the pigs.” Soon many demonstrators were carrying mace, baseball bats and other increasingly hostile weapons --- not a good sign given that a rifle was the official Venceremos logo.

Two Saturdays later, under guidance from Mayor Jack Wheatley and City Manager George Morgan, police tried backing off. More than 200 officers watched from a distance as a rock band played on until 1 in the morning.

But many radicals wanted to draw police into a confrontation. In August 1971, students at the Plaza goaded police in a series of escalating steps. As then reporter Jay Thorwaldson described, “between each step, there was a few minutes wait, either to build up nerve for the next step, or more likely, to see if there would be a police response.” After starting several trash fires and pulling a number of false box alarms, demonstrators blocked Emerson Street with a bicycle rack, dumped over a trash bin, severely damaged and set a newspaper rack ablaze. They then set out to break more than $24,000 worth of windows along University Avenue. Weeks later more than 20 trash containers were set on fire and rioting concert-goers broke light fixtures and defaced property with slogans like “Kill the pigs.”

While things finally began to calm down over the next summer, the legacy left at Lytton Plaza was not exactly the soulful refrain of “We Shall Overcome.”

Eventually, Lytton Savings Bank was bought out and the city purchased the space from its new owner. Since those days, Lytton Plaza has continued to be Palo Alto’s traditional place of protest, although it’s been some time since the teargas machines have been needed.

Recently, there have been plans bouncing around City Hall to tear up Lytton Plaza and replace it with a new park full of leafy trees, pretty hedges and a waterfall. Gone will be the cement benches and concrete austerity. Perhaps it will be a new start for the aging plaza with so many memories that no one particularly wants to remember. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

Send Us Your Memory!

Lytton Plaza in 1964. (PAHA)

A Venceremos rally at Lytton Plaza.

Lytton Plaza in the 1980s with Burger King in the background. (PAHA)

The American Trust Company Bank is where Lytton Plaza once was. (PAHA)

Lytton Plaza after a recent revamping. (PA Weekly)