The Humane Society: A History of Compassion

There was a time when the life of a city animal was a lot less domesticated than it is today. Before the advent of leash laws, license tags, pooper scoopers and pet daycare, city life for dogs and cats ran a little closer to the wild side. Without the laws that have set today’s familiar pet and master routines, our four-legged friends enjoyed an independence that allowed them to roam the neighborhoods and seek out adventure. Today, some longtime pet lovers may still have fond memories for those old neighborhood dogs waiting for their young masters outside the school each day or chasing down speeding cars. But of course, with such adventures also came the danger and potential cruelties of a life not so sheltered by an owner with leash in hand. Luckily, in early day Palo Alto there was a group of concerned citizens always looking out for the city’s furry friends.

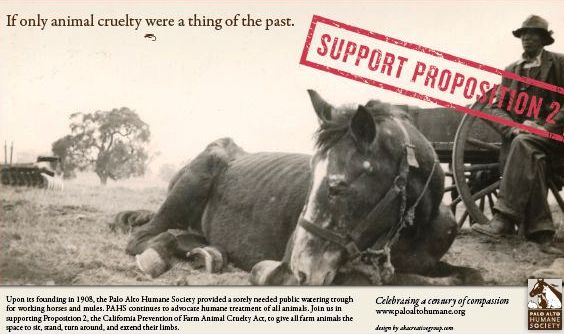

In 2008, the Palo Alto Humane Society celebrated its 100th birthday as protector of Palo Alto’s animal population. This nonprofit group has been responsible through the years for such tasks as running the city pound, treating hurt and stray animals, monitoring the conditions of farm animals and preventing animal cruelty. It has been said that a society is ultimately judged by how it treats its weakest and most vulnerable members. If so, then Palo Alto owes a debt of gratitude for the more than 100 years of service that the PAHS has spent advocating for the city’s animal voiceless and vulnerable.

The Palo Alto Humane Society’s long history dates back to old Mrs. B.C. Merriman, who as legend has it once rode the Palo Alto streets whip in hand, ready to teach a lesson to any driver she saw mistreating his horse. In 1902, the founding members of the Society's predecessor Palo Alto SPCA included Stanford’s first president, David Starr Jordan and Jane Stanford herself, both of whom helped push for the city’s first horse watering trough in the days before automobiles. In 1908, the Society renamed itself to become the Palo Alto Humane Society.

But it wasn’t really until 1924 that the PAHS found its voice. That year Police Chief C.F. Noble ordered a crackdown on dogs roaming the streets without licenses. Playing the villain to a tee, Noble hired a man called Dick the Dogcatcher to enforce justice. Soon the papers were full of letters from readers complaining about maimed dogs that had been swiped from their home yards and porches. One man wrote in to the Palo Alto Times complaining that his dog had never been the same after it was impounded, saying that it had returned home a “wild-eyed creature with deep bites about the head and body.” There was also some history of the local police operating with a “shoot on site” policy for strays.

Clearly, there was a need for the Humane Society to help safeguard the city’s pets and strays from this rather overzealous police force. But the PAHS had little money and no land on which to construct a shelter. Enter, Mrs. Frank Thomas (as she was always called in the papers of the day), a Middlefield Road resident who was known for taking in as many stray pets as her home and husband would allow. Before long, the PAHS had set up kennels in her yard and acquired her services to take care of the animals being rounded up all over the city. And although it was supposed to be just a temporary arrangement, Mrs. Thomas wound up donating her home and time for more than two years before the city spent $2000 to build a makeshift pound.

A decade later, the PAHS was able to finally build a first-rate shelter thanks in part to an $11,000 donation from Mrs. Marguerite Ravenscroft of Santa Barbara. The new quarters built in 1937 at the current location of El Camino’s Sheraton Hotel, was described by the Palo Alto Times in 1947 as a kind of “animal utopia,” complete with air-conditioning, heating and beds for some 50 dogs and 25 cats. The shelter also included full kitchen service for animal meal preparation, one-way receiving kennels where lost animals could be dropped off after hours and a tiled tub for bathing dogs.

Indeed, contemporary newspaper accounts tell of a happy animal atmosphere full of characters such as Trigger, a quick and feisty feline who after catching her daily allotment of mice and rats, would head out to the parking lot to clear out the gophers. Moving at a slower pace was Ol' Pa, a desert turtle who enjoyed promenading along the kennel fence torturing the yelping puppies below.

But the shelter took care of more than just dogs, cats and the occasional turtle. Monkeys, raccoons, porcupines, ducks, turtles and skunks all found their way onto the shelter roster in those days --- not to mention a rare visit from a wolf or a crocodile. The shelter also employed an ambulance service for sick and injured animals around town. During World War II, the Society was able to use its vehicle capabilities to save dozens of animals that Japanese Americans were forced to leave behind during their internment in war relocation camps authorized by U.S. Executive Order 9066.

Education has always been an important tenet of the Palo Alto Humane Society’s mission. In its early days, the PAHS visited schools to teach children the proper way to treat animals through films, poster contests and parades --- even organizing “Bands of Mercy” to encourage children to keep an eye out for local animals in need.

But when educating the community was not enough, the Society was not

afraid to use legal action to protect animals in Palo Alto. For instance, the PAHS’s annual report from 1939 details how five offenders were taken before judges that year after failing to heed the Humane Society’s warnings for improperly chaining their dogs. In 1984, the PAHS brought a lawsuit against Stanford University and the Veterans Administration for abuse in the care of a white Samoyed dog named Snowball who was found in pain with open wounds and incisions.

When legal action was not possible, the Society sometimes found other ways to help animals in need. In one case, the PAHS purchased a blind horse to take it out of the “horse-trading racket,” putting it out to pasture with other older horses at Mrs. Frances Newhall Wood’s appropriately-named Hawthorne Happy Home

for Horses. Other times the Society’s work took them off the Peninsula. During the terrible Sacramento River floods of 1940, PAHS officers travelled more than 21,000 miles to rescue stray, sick and abandonedanimals.

During the 1960s, the Humane Society responded to the times by becoming more involved in political issues. For instance, in 1961 PAHS President Gerald Dalmadge took a firm stand against Stanford University School of Medicine’s desire to use the shelter’s unclaimed animals for research. Citing the agreement with which Mrs. Ravenscroft had given $11,000 to help built the shelter in 1937, Dalmadge said that it would be a “violation of the principles under which the

shelter was established.” Eventually Stanford withdrew its request, citing “strong public reaction.”

In 1972 the Humane Society ceded control of the shelter to the city. Since that time, the PAHS has remained heavily involved in advocacy and education --- or as they put it: “Instead of managing animals inside a shelter, we work to keep animals out of the shelter.” They neuter 1,000 homeless animals and pets in need annually, provide for emergency rescue care, maintain a hotline for animal related questions and are designing an elementary classroom curriculum for California schools.

In the past two decades, the PAHS has also flexed political muscle by rallying against greyhound racing, steel jaw leghold traps and decompression chambers for euthanizing shelter animals. PAHS has also launched Humane Planet, a program to promote humane dining options and certify restaurants and caterers that meet specific standards.

In 2008, the PAHS fought hard for Proposition 2, a state ballot initiative that sought to eliminate the cruel confinement of California farm animals. Indeed, the passage of Prop 2 demonstrates that while Dick the Dogcatcher may be long gone, there is still much to do as the Palo Alto Humane Society heads into its second century. []

Our Reader's Memories:

"No, I wasn't around in those days, but when I was a kid in the mid-1960's, our Girl Scout troop took a hike down San Francisquito Creek. The story goes that when the Stanford Chapel was damaged in the 1906 quake, the broken tiles from the mosaics were thrown into the creek. We dug around a bit and found all kinds of colorful tiles in the

creek bed."

-T

Send Us Your Memory!

The new Palo Alto animal shelter in 1937. (PAHA)

A dog's life was much less inhibited in the city's early days. (PAHA)

Former PAHS president Gerald Dalmadge makes a friend. (PAHA)

The PAHS lobbied hard in support of Prop 2 in 2008.

The original city pound as seen in 1927. (PAHA)