Save the Oaks: Palo Alto's First Environmental Victory

In the 20th Century urban environments were overhauled to suit the automobile. As the early “horseless carriage” --- a novelty toy for the rich --- was transformed into an essential appliance of the American Dream, the environment changed to accommodate this new way of life. In the 1920s, new roads and highways crisscrossed the country linking small towns and large cities. In the 1950s, the interstate highway system sent freeways and turnpikes over farmland, across pastoral vistas, and up (and sometimes through) mountains ranges.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, highways headed for downtown, often dividing urban neighborhoods right down the middle, forcing out tenants and homeowners through the power of eminent domain. And urban main streets became increasingly suited to the automobile. Parking lots, endless strip malls (with acres of convenient parking), and six and eight lane boulevards were built to deal with ever worsening urban traffic and parking problems. Today, cities like Los Angeles are now virtually enemy territory for pedestrians who are often forced to walk downtown in elevated walkways connecting office buildings. Even in a smaller city like Palo Alto, crossing a car-friendly “traffic artery” like El Camino Real is no treat.

Not that there haven’t been those who have tried to stop the ever expanding empire of the automobile. Locally, former Mayor Yoriko Kishimoto has been a consistent supporter of the concept of the “walkable city,” backing shuttles, bike lanes, farmer's markets and even favoring temporary day-long conversions of University Avenue to a pedestrian plaza.

But Palo Alto’s first environmentalists to fight automobile dominance were those who battled to “Save the Oaks” in 1914. These were early days for the automobile, just six years after Henry Ford’s first Model T “put America on wheels.” Still, there were already some 225 automobiles in the Palo Alto area, zigging and zagging through city streets avoiding horses, carriages, pedestrians and sometimes trees.

Indeed, if the car now reigns supreme in American culture, it didn’t even have the roadway to itself in 1914. Some 132 oak trees stood in 25 Palo Alto streets, often right in the center of the road. Bryant Street had eleven oaks in just twelve blocks and thirteen oaks stood in Cowper street over a thirteen-block distance. Since horse-drawn buggies had little difficulty navigating the occasional road-blocking tree, Palo Alto’s original street grids simply let the trees stand as they had hundreds of years.

But cars and trees did not share the road so easily. Without street lights, warning signs, or windshield wipers, drivers in unfavorable conditions had a tendency to run headlong into these beautiful old oaks. This was the case in early 1914 when Dr. Benjamin Thomas smashed head-on into a Bryant Street oak, creating an eight-inch gash in the mature tree. He claimed that city officials were negligent for allowing such a dangerous object to remain in the street and sued for $5,000.

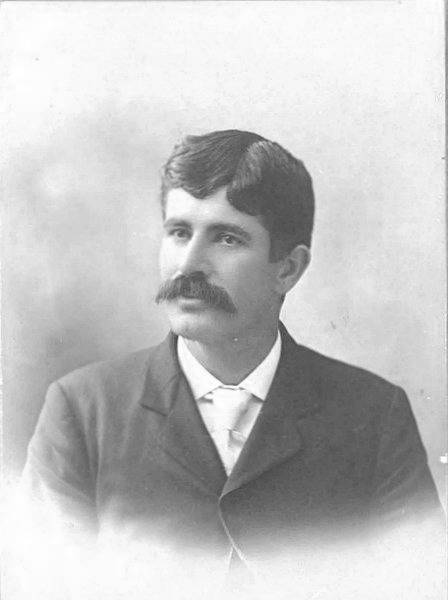

Although he eventually lost, during the progression of the case through the courts, Palo Alto’s City Council considered handing over the streets to the automobile permanently. Many feared that more injuries and lawsuits lay ahead if the trees remained. Sure enough, Palo Alto Councilman George Mosher drove his car into a tree during the months that the Council was considering the issue and later that year Mrs. H. J. Moule slammed into the same tree as Dr. Thomas. In fact, the Palo Alto Times reported in 1915, rather incredibly, that a dozen cars crashed into that one tree over a two-year period, making one wonder if the tree didn’t have some sort of otherworldly magnetic pull.

Debate was heated on both sides of the tree question. Palo Alto’s noted environmental sensibilities were apparent even in this era in the assertions that the trees should remain. One woman pleaded to Palo Altans in a Times Op-Ed to “Save their lives! With what infinite patience have they persisted through the stress of many years, offering protection to man and beast with arms continuously outstretched in love and benediction to all. No, you cannot take the life of such friends and benefactors.”

Some even felt that the threat of a dangerous tree lurking down a dark street could be a beneficial incentive for drivers to slow down. Several hundred school children signed a petition to the City Council to spare the oaks and one advocate wrote dreamily of twin trees on Cowper Street, “a Gothic arch…shaped perfectly by the Creator’s hand… and placed at the gateway to our city.”

But others believed that the center-lane trees were an obstacle to progress, including nine out of fifteen city council members. In an 1,100 word leaflet distributed to some 1,500 Palo Altans, Councilman E.A. Hettinger argued in favor of his proposal to remove any oak standing within the “driveway part of any street from gutter to gutter.” He then placed a rather heavy burden on the voters, warning that “if you cast your vote to leave these obstructions to jeopardize life and property --- these perilous monuments to sentiment --- and a life is lost, your conscious must be your accuser for you have voluntarily shared in the blame.”

Another advocate, I.A. Fickel, perhaps more reasonably, contended that, “The auto has come to stay and its increase in the next 10 years will be marvelous…we have got to adjust ourselves to a faster life…every means must be used to keep the roadway clear of obstructions.”

On September 11, 1914, Palo Alto voters went to the polls to decide the fate of the trees. They soundly defeated the Hettinger plan to eliminate all street trees by a vote of 528-308. The fate of each tree was then to be determined by the council individually, resulting in many trees later being “whitewashed” near their base to make them easier to see on a dark night. Today you can still find an occasional whitewashed tree in Palo Alto.

Of course, in the end the trees were fighting a hopeless battle against the revving engines of modernity. Little by little, the oaks were brought down, clearing the way for the automobile to dominate the center of both the road and American society. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

Send Us Your Memory!

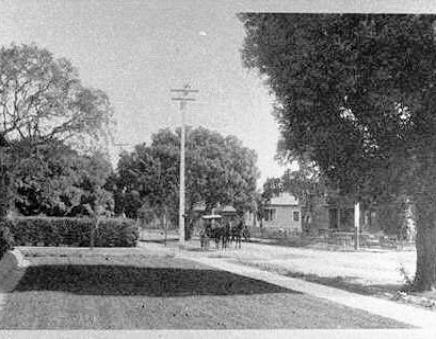

A tree stands in the way near Bryant and Lincoln. (PAHA)

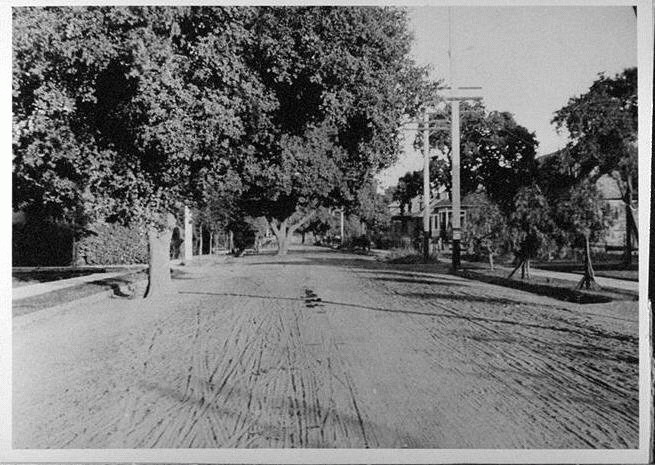

University Avenue from Hale Street where trolleys had to avoid the trees. (PAHA)

A tree stands in the center further down Bryant Street. (PAHA)

A tree still stands partially in the street on Cowper.

Councilman George Mosher found that oak trees in the middle of streets could be a problem. (PAHA)