The Circus: Greatest Show in Palo Alto

There was a time when there was no bigger day in an American small town than Circus Day. It’s a little hard to imagine the magnitude of this yearly event now, in part because we’ve forgotten the remote isolation of small towns in the early part of the 20th Century. Before television, radio and the Hollywood movie, small town folk did not have the digitally connected living room that they do today. The geographical isolation was also far more dramatic in those days. Cities had not yet sprawled out into the heartland and the lack of highways and passenger planes meant that millions of Americans would never travel more than a few hundred miles from their place of birth. So when the real circus came to town, it was a very big deal. And though one circus may still call itself “The Greatest Show on Earth,” in those days the circus was also the only show in town.

Of course Palo Alto was not exactly isolated, even in its earliest incarnation. Not only was it a major university town but it was also just a short train ride away from the biggest city on the west coast. Still, a look back at pioneer Palo Alto finds a sleepy town that hardly resembles the techie center we know today. Even into the 1930s and '40s --- and arguably beyond--- Palo Alto was still a quiet little hamlet with the entertainment options to match.

So on circus day, the town came to a virtual halt. A Palo Alto Times headline from the 1920s makes this clear by announcing that Palo Alto schools would have a “circus holiday.” School authorities, the paper reported, reasoned that “children’s minds are not receptive to ‘book learning’ when the circus is in town.”

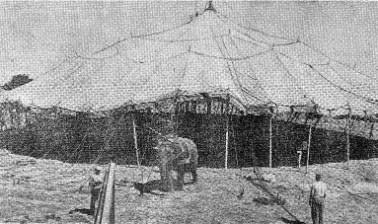

Of course, the circus was virtually a town of its own. Often taking up two or three dozen railroad cars, the circus would arrive at the University Avenue Station. A frantic move would then take place as hundreds of employees would transport the enormous production to one of the circus locations --- usually an open field.

Actually, both of the main Palo Alto circus locations would become future shopping centers--- the John Greer property where Town & Country Village now stands and the empty lot where one now finds Edgewood Plaza. Here workers would drive huge spikes into the ground, raise the big top and set up a small city dedicated to laughs and thrills.

And a city it was. A 1936 Palo Alto Times story told of the arrival of the “city within a city” of the 1,080 member Cole Brothers Circus: “This ‘city of white tops’ which flits around the country has its own postmaster, garage, physician, lawyer, drug store, detectives, barber shop, wheelwright and blacksmith shops.”

On the day of the big show, the atmosphere was often hurried and hectic. Usually a circus representative would hustle over to Police Court on Bryant Street to get a permit and invite the fire and safety inspectors back to camp. As Building Inspector Joe Salameda told Times editor Elinor Cogswell in her “Editor at Bat” column in 1948, “Everything is hurly-burly. A public relations man takes you over and rushes you around…free passes are being handed out. They capitalize on the confusion.” And of course, heaven help the inspector who actually had to tell the public that the circus had been cancelled.

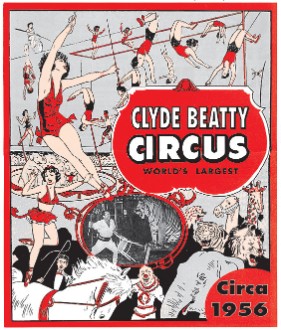

Many different circuses came through Palo Alto over the years, and they were almost all crowd-pleasers. A look back at some of the touring the acts gives a hint of the excitement. Roy Ring’s Bicycle Riding Monkey “Tony,” Tillie the Fan Dancing Elephant, Dardenella, the Rose of the Orient, Madame Golda and her $10,000 Dancing Horse “White Pearl,” and even a pair of “Boxing Horses, direct from England” all delighted the crowds in Palo Alto. Posters advertised the action. Who would want to pass up a chance to see “Clyde Beatty in person shaking dice with death in the big steel cage with 40 cruel, blood-thirsty lions and tigers of opposite sexes”?

But it wasn’t always just lions, tigers, clowns and stunts. For instance, when the Barnes Circus arrived in April of 1925, they accompanied traditional acts with a “pageant enacting the adventures of Captain John Smith and his rescue by the Indian Girl Pocahontas.” Wild West themes highlighted such shows as the Congress of All-Western Champion Cowboys, Ken Maynard’s Wild West, and the 101 Ranch and Wild West Show. The 101 Ranch frantically advertised that the audience would be treated to “An Indian Massacre! A Stage Coach Holdup! And an Outlaw attack on the Emigrant Train!”

Despite the breathless posters and banner headlines, not everything always went exactly as planned. In 1946, for instance, the Clyde Beatty Circus needed the help of police escorts when a railroad strike resulted in the slow plod of the entire circus --- pachyderms and all --- up El Camino by foot to the

next show in Redwood City.

That was nothing compared to the fate of the Palmer Brothers Wild Animal Circus back in November 1921. The entire outfit was stranded in Palo Alto when Mr. Palmer himself took off with all the door receipts as well as the “fat girl, midget maiden, African pigmy boy and Australian bushman,” according to the Palo Alto Times. Left behind were 190 unpaid employees who took refuge in town waiting for more than $10,000 in past due wages. With Mr. Palmer long gone and no money to keep the circus going, the Times reported days later that many residents were beginning to complain of the “noise of the caged animals” and of "a sanitation problem that has developed.” The complaints prompted city authorities to order the circus to leave, charging $100 a day for its use of city land. Eventually, Palmer’s abandoned circus was purchased by another proprietor and the animals were deposited at the Palo Alto Stock Farm.

The city always did what it could to help the show go on. One September night in 1942, scores of local boys were pressed into service when the Cole Brothers Circus arrived short of help because the draft had sent many workers into the army. Each boy received a free pass to the show in exchange for his help. One rainy evening in 1946 several hundred eager Palo Alto children and their parents waited more than an hour for the show to start even though the Times reported that “the tent leaked in a thousand places and the ground was ankle deep in mud and straw.” Some of those waiting might have recalled that in earlier for years, the city served as a kind of winter base for a number of circuses as they retooled and made repairs before setting out for another season's tour of the country. Howe’s Great London Circus spent four months one winter at the old remount station and spent some $125,000 in town, while during the winter of 1917-1918 the Bernardi Circus’s 23 railroad cars parked themselves in Palo Alto.

Eventually, the unique excitement of circus days would pass as television, movies, sporting events and other forms of entertainment increasingly dominated. Fewer circuses were able to survive the great expense of moving from town to town at such a pace. The rising costs of gasoline, big tops, and food for the animals all made travelling circuses an increasingly unprofitable business. In Palo Alto, circus days essentially ended in 1953 with the construction of Town & Country Village. By then the circus Big Top was already an endangered species. Eventually the old-time travelling circuses died out, leaving the surviving conglomerates to play indoors in arenas built for ice hockey and basketball. Today’s kids see their share of the wonderful and the marvelous on screens big and small, but it’s just not the same as sitting a few rows from a dancing elephant or a bicycle-riding monkey. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

Send Us Your Memory!

A circus at the future site of Town and Country Village.

Town and Country Village was built on a popular lot for circuses.

The Clyde Beatty Circus was a frequent and popular visitor to Palo Alto.