Palo Alto's Homefront: Life During Wartime

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, they awoke a sleeping giant --- the American economic machine that Franklin Roosevelt had once called, “the arsenal of democracy.” Although the United States had been mired in ten years of economic depression and was initially weary of war, it rallied to counter the humiliation of Pearl Harbor. The country soon began a steady progression toward the massive wartime economy that would eventually affect almost every aspect of life on the home front. In many ways, this domestic transformation was just as important as the fighting taking place overseas. For once America’s mighty economic engine had been ignited; defeat was more or less in the cards for its enemies.

What war meant to Americans at home was different during World War II than in any subsequent American war. From Korea to Vietnam to the Gulf War, Afghanistan and Iraq, Americans have had the luxury of sending off their military personnel to foreign lands to their usual daily lives with little change. But the sheer size and scope of the Second World War meant that every American got the call from Uncle Sam in one way or another.

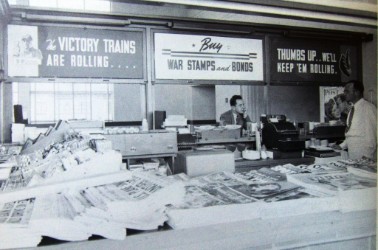

As a west coast city, Palo Alto was heavily involved in the war effort. The city certainly sent its share of soldiers overseas --- from Palo Alto High School alone, 73 graduates died for their country. But those back home were also invited --- sometimes virtually compelled --- by the government to do their part. A review of wartime posters finds that Palo Altans, like the rest of country, were called upon to “buy war bonds,” “take your place in civil defense,” “share the meat,” “save your tires,” “eat the right food,” even “button your lip.”

Still, America’s propaganda machine spoke what was an essential truth --- the key to American victory lay in the effort of civilians at home. And indeed that word “victory” seemed to be everywhere. Americans were asked to drive at special “victory speeds” to save rubber --- just 35 mph on the highways. The government urged Americans to prepare “victory homes,” which according to ads from the Palo Alto Hardware Company necessitated essentials such as the Plumb Defensax --- an air raid safety tool in case of foreign attack. Men wore “victory suits” that used less cotton by fashioning narrow lapels and short coats while an Office of Price Administration “victory cookbook” offered meals heavy on non-rationed ingredients.

Of course, there were also the famed “victory gardens” in which average Americans helpedprotect the public food supply by growing their own vegetables in the backyard. Originally, promoted by Secretary of Agriculture Claude R. Wickard as a civil morale booster, more than twenty million victory gardens flourished nationwide including hundreds in Palo Alto. In October 1943, Jordan Junior High Schoolers boasted a victory garden that produced “one ton of foodstuff --- the amount an average soldier consumes in a year.”

And there were still other ways that those on the home front could contribute. Housewives saved kitchen fat in jars, which later could be turned into the glycerin used in explosives. In one Liberty magazine spread, two sailors ogled elegant Hollywood actress Helen Hayes handing a jar of fat to a grocer as she told

housewives that “a single pound of kitchen grease will make two anti-aircraft shells.” And kids found they were essential as well in scrounging for metals and rubber for scrap drives. Local kids peeled foil out of cigarette packs and gum wrappers while wearing government issued banners reading “Slap the Jap right off the map by Salvaging Scrap!”

Palo Altans, like all Americans, were also called to sacrifice during the war years. Volunteer workers at the Palo Alto Ration Board placed limits on such items as sugar, meat, butter, coffee, gasoline, tires --- even typewriters. The strict limitations on driving led to a comeback by the bicycle. The Palo Alto Times reported to readers that, “the automobile replaced the horse and now the bicycle has replaced the automobile.” Crammed racks of bikes were everywhere along University Avenue during the war years as tire rationing was severe. During the entire month of February 1942, the entire city was allowed just eighteen car tires. And Palo Altans had to get used to going without. The Times reported that “folks wait weeks for laundry without a peep for fear of being cut off the driver’s list” while “shoes wait weeks for repair in local cobbler shops short of help.”

With so much of the nation’s workforce on battlefields in Europe and at sea in the South Pacific, the American labor market saw wholesale changes. Famously, women were pressed into traditionally male professions from bank tellers to factory workers. Still, it was hard to forget that such advances were due more to necessity than open minds. A 1944 Palo Alto Times news piece sounds a rather patronizing tone: “Many a man realizes now how competent the girls are at his old jobs. In [Palo Alto] they have pitched in and ‘manned’ taxis, buses, the cannery, gas stations, the banks, the post office. Let ‘em stay on after the war, we say, leaving the men to hunt and fish --- as God intended.” And a 1943 article exclaimed that “it’s fashionable to be useful, as well as beautiful, this year,” as it told of how nearly forty Palo Alto women trained for Stanford drafting, chemical analysis and industrial accounting courses were on their way to finding jobs at

Bay Area war plants.

Other housewives served in other ways. Hundreds of volunteers rolled bandages for the Palo Alto Red Cross, while one Palo Altan, Mrs. Walter Rodgers (as she was always identified in the press) opened “Hospitality House” in her own residence, tallying a guest book registration of over 50,000 by 1944. During the 1943 Christmas she organized the transport to soldiers abroad of some 700 individually-wrapped giftsdonated by Palo Altans.

Finally, a little after four on the afternoon of August 14th, 1945, reports began to circulate throughout the city that the Japanese had surrendered. As in most parts of the country, an impromptu party immediately broke out. A city siren appropriately malfunctioned and blared for a quarter of an hour as firecrackers were lit and makeshift confetti thrown. One woman gleefully marched down University Avenue banging a milk bottle against an ice cream freezer and cars packed with young men from Stanford’s army training corps --- some in full battle regalia --- rolled into town with horns honking. Youngsters ripped American flags from J.C. Penney’s and the Hotel President and waved them excitedly while the Stanford Band marched down University Avenue to the Stanford Theatre where they triumphantly played “The Star Spangled Banner.” At last it was all over. After more than three and a half years of rations, shortages, blackouts and worries, success was finally at hand. Victory had been hard-earned, peace had arrived, the future was bright. []

Our Reader's Memories:

"This was a comprehensive and very interesting article about how WWII affected Palo Alto. An additional area that I suggest for future consideration: Dibble Hospital, where SRI and public parks now stand, was home for many returning soldiers who had been seriously injured in WWII.

In Palo Alto and Menlo Park, we saw some who suffered from shell-shock, along with amputees, and others with serious injuries and psychological damage."

-Don

Send Us Your Memories!

A war bonds and stamps truck downtown in Palo Alto. (PAHA)

A rubber drive in Palo Alto. (PAHA)

The Victory Trains were rolling at the downtown post office. (PAHA)

A war bond drive at the Stanford Theatre. (PAHA)

They All Kissed the Bride was playing at the Stanford Theatre during a war bonds drive. (PAHA)

A victory garden in Palo Alto during World War II. (PAHA)