William Shockley: Paranoia Runs Deep

It is unlikely that any Palo Altan has ever lived a life as important as William Shockley. As a young man during World War II, he won the nation’s highest civilian honor for discoveries that saved thousands of lives. In 1956, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics for the invention of the transistor, a device that either made possible or greatly improved nearly every modern gadget we use today. He then moved west and started the company that became the catalyst for the rise of Silicon Valley. He was even named one of the 100 most important people of the 20th Century by Time Magazine in 1999.

And yet despite this resume of accomplishment and his indisputable intelligence, William Shockley always seemed to find a way to allow his personality to spoil his own success. Throughout his 79 years, Shockley threw tantrums, fought petty disputes and turned his friends into enemies. He divorced his first wife, severed relations with his children and forced his brightest employees to leave his company and outshine him elsewhere. Finally, as an angry and bitter man in his retirement years, Shockley became the champion of an angry and bitter theory. His association with it would bring him scorn, ridicule and deep contempt from the scientific community and the broader public. In the end, his reputation in tatters and his accomplishments largely overshadowed, William Shockley would die friendless and ignored, his own worst enemy.

William Shockley seemed to enter the world in the midst of a fight. Born in London in 1910 to American parents, Shockley’s early childhood was something between tempestuous and the taming of a beast. When William was just a month old, his father wrote in his diary that his child “gives signs of having a violent temper.” Indeed, he was soon biting and slapping his parents, who seemed completely incapable of coping with their son’s rage. “It is an odd day when he does not break something,” his father would write during William’s toddler years. At three years old, he hit a Dachshund between the eyes with a stone and one day during his usual mealtime screaming fit, rocked his chair back, flipped it over and injured his head on a metal radiator.

In 1913, the Shockleys moved to Palo Alto and lived in a small house at 959 Waverley Street. Economic instability and his parents’ obsession for complete privacy later led to a series of relocations from one downtown home to another. In Palo Alto, William’s temper improved little at first. But ignoring psychiatric recommendations for more socialization, his parents decided to home school William until age eight. Finally, feeling they were unable to keep him out of a school setting any longer, they sent him to the Homer Avenue School for two years, where his behavior improved dramatically --- he even earned an “A” in comportment in his first year. As a teenager, William received more discipline at the Palo Alto Military Academy. As his biographer Joel Shurkin says, “Bill had learned to control his temper out in the world, saving it for [his parents] where it was most useful.” After his father’s death in 1925, he and his mother moved to Hollywood where William eventually entered Caltech to pursue a degree in physics.

After earning his Ph. D. from MIT and gaining employment at prestigious Bell Labs, the New Jersey research wing of AT&T, Shockley’s plans would be sidetracked by Pearl Harbor. But his accomplishments in the next three-plus war years were astounding. It has been said that he saved thousands of lives without ever leaving his desk, mostly through his work advancing Allied techniques for using radar equipment and depth charges. Later, he completely redesigned the training procedures for American bomber crews. Near the end of the war, he became an expert consultant to the office of the Secretary of War --- making him one of the highest ranked civilian scientists outside of Los Alamos. Remarkably, even before the war had begun, he and colleague James Fisk, quite by accident, designed a nuclear reactor similar to the Manhattan Project discovery that would lead to the Atomic Bomb. For all his war efforts, Shockley was awarded the National Medal of Merit.

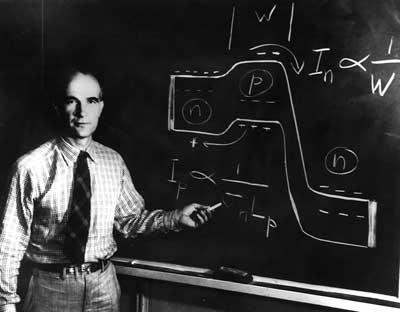

Returning to Ma Bell after the war, Shockley was placed at the head of the 34-man Solid State Physics Team, where Shockley oversaw a team of brilliant physicists including John Bardeen and Walter H. Brattain. Their task: To find a smaller and reliable alternative to the fragile and bulky glass vacuum tube amplifiers that would not allow for a decent coast-to-coast call. Often sitting at a blackboard, trading theories and hypotheses, Shockley’s team used what he would later call “creative failure methodology.”

After a series of trial and error setbacks and detours, Bardeen and Brattain finally broke through during the “magic month” of December 1947, inventing what would come to be called the transistor. And while Bell Labs quite rightly gave Shockley full credit as team leader, he would spend the next few years fuming over having had to learn of the great discovery over the phone.

After the discovery, Shockley worked tirelessly to add to the invention. In his efforts, he invented an even stronger amplifying device --- the junction transistor --- and then forged ahead to author what would become the seminal work of his field, Electrons and Holes in Semiconductors, published in 1950.

The Shockley transistor would lead to other advances in transistor technology, eventually creating a vast new industry that sat at the heart of all modern electronics. As Joel Shurkin writes, “ Every transistor that powers the electronic age, the tens of millions now in our homes and offices, in our computers, watches, ovens, airplanes, CAT scan equipment, cars, fax machines, cameras, spaceships, and yes, our telephones, is a descendant of that device. Shockley's feat… was his life's greatest accomplishment. It changed the world.”

Shockley then headed back west to further his invention and make some money off it --- opening up shop at 391 San Antonio Road in Mountain View, essentially Silicon Valley’s first startup. Shockley had a great eye for talent and since none of his Bell Labs colleagues would join him (he had by then ostracized Bardeen, Brattain and most of the others), Shockley hired the best and the brightest from nearby engineering schools.

But Shockley’s managerial style would prove severe and suspicious. As one friend would observe, Shockley had a kind of reverse charisma --- when he walked into a room, you instantly took a disliking to him. In one bizarre incident, when a company secretary cut her thumb on a thumbtack that had been stuck in the door, Shockley demanded that his employees take lie detector tests to find out how it got there.

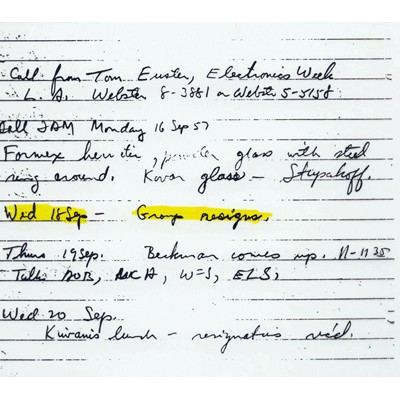

Eventually, the paranoia would lead to the 1957 defection of the so-called “Treacherous Eight,” who fled Shockley Superconductor to form rival Fairchild Semiconductor --- eventually producing the first integrated circuits and beating their former boss to the punch. Many of the “Treacherous Eight” would later start spinoff companies, including Intel and National Semiconductor, ushering in the next generation of Silicon Valley. They would also manage to get rich while Shockley’s company tanked.

In the 1960s after taking a professorship at Stanford University, Shockley became nearly obsessed with genetics --- a field in which he was untrained, but incredibly passionate. In 1965, he preached at a conference that the human race was threatened by a “genetic deterioration" and the

attention he received from a U.S. News & World Report interview a month later further fueled his desire for verbal combat. His views became increasingly controversial, as he asserted that darker races were mentally inferior to whites and that ghetto blacks were “downbreeding” humanity. He became a firm proponent of eugenics: the belief that targeted breeding could lead to improvements in the human race. At age 68, he even donated to a California sperm bank for geniuses --- not long after calling his two sons and daughter an evolutionary “regression.”

Controversy and rage followed him everywhere and he welcomed it. Talking of prejudice against blacks in 1980, he told Playboy Magazine, “If you found a breed of dog that was unreliable and temperamental, why shouldn't you regard it in a less favorable light?" He was the subject of rallies where he was called the “Hitler of the ‘80s.” His classes and speeches were frequently interrupted by protesters, and he once debated face-to-face with Stanford protesters who burned him in effigy. By 1982, Shockley was running for the California Republican Party's Senate nomination on a platform advocating voluntary sterilization for those with an IQ under 100. He would finish in eighth place with less than one percent of the vote.

In 1989, Shockley would die in disgrace at the age of 79. He was all alone except for his second wife, Emmy, who did not hold funeral services because no one would have attended. His children learned of his death by reading the newspaper. []

Send Us Your Memory!

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

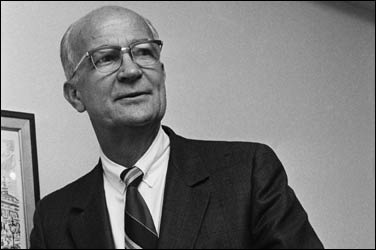

William Shockley in 1971.

Shockley Transistor on San Antonio Road in Mountain View.

One of the Shockley's childhood homes at 959 Waverley Street.

Young William Shockley at the blackboard.

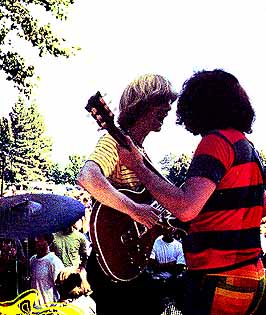

The Shockley team toasts their leader before many would exit the company.

William Shockley's brief mention of the departure of defection of the "Treacherous Eight."

The house on Waverley Street today.